By the beginning of 1915, four months after Britain declared war on Germany, the conflict in Europe was at a standstill. Thousands of miles of trenches crisscrossed Belgium and northern France, and anyone poking their head above ground was liable to attract a sniper’s attention. Desperate to break the stalemate, a young Winston Churchill pushed a plan to attack the Central powers from behind, by invading Turkey. If successful, the opening would allow the Allies to deliver much-needed supplies to the Russians on the Eastern Front and potentially swing the war in the Allies’ favor.

Allied generals believed Gallipoli, a dry peninsula jutting out into the Aegean Sea, was the key to establishing a foothold in Turkey. But the Allied planners underestimated the resistance they would face and didn’t plan for the near-impassable geography: after six months of naval and land assaults the British, French, Australian, and New Zealand soldiers fighting in Turkey had sustained many casualties but taken little land. In August, Allied commanders hatched a scheme to capture a ridge in the center of the peninsula to gain the advantage of higher ground. Among those deployed was a unit of inexperienced Brits sent on a night march through treacherous, boulder-filled gullies.

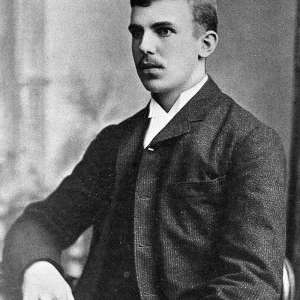

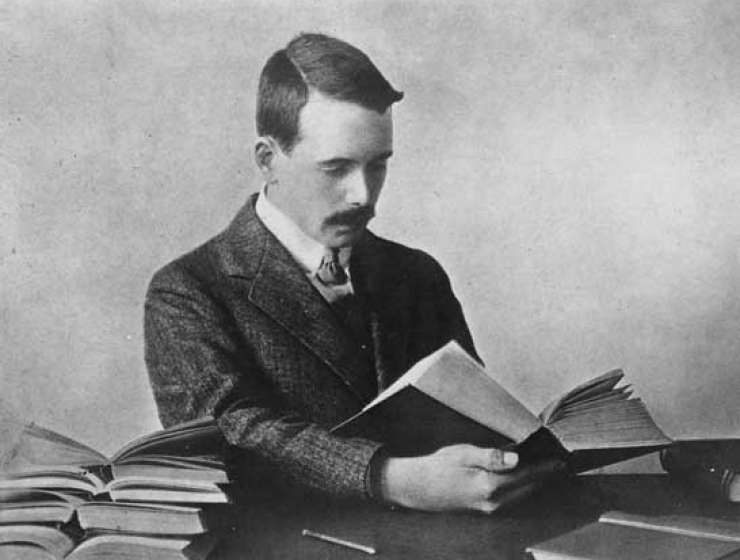

The soldiers never reached their destination. While stumbling through the unfamiliar terrain they came under attack from 30,000 Ottoman troops supported by machine guns. It was a slaughter. Among the British dead was a promising young physicist who had reshaped the periodic table just before shipping off to war, and his death would reshape the way militaries determined who was and was not sent to war.