Ibn Arabi (1165-1240)

How can the heart travel to God, when it is chained by its desires?

Ibn ʿArabi, full name Abu ʿAbd Allah Muḥammad ibn ʿAli ibn Muḥammad ibnʿArabi al-Ḥatimi at-Ṭaʾi al-Andalusi al-Mursi al-Dimashqi, nicknamed al-Qushayri and Sultan al-'Arifin was an Arab Andalusian Muslim scholar, mystic, poet, and philosopher, whose works have grown to be very influential beyond the Musliim world. Out of the 850 works attributed to him, some 700 are authentic while over 400 are still extant. His cosmological teachings became the dominant worldview in many parts of the Islamic world.

He is renowned among practitioners of Sufism by the names al-Shaykh al-Akbar "the Greatest Shaykh"; from here the Akbariyya or Akbarian school derives its name, Muḥyiddin ibn Arabi, and was considered a saint. He was also known as Shaikh-e-Akbar Mohi-ud-Din Ibn-e-Arabi throughout the Middle East.

Biography

'Abu 'Abdullah Muḥammad ibn 'Ali ibn Muḥammad ibn `Arabi al-Hatimi at-Ṭaʾi was a Sufi mystic, poet, and philosopher born in Murcia, Spain.

Ibn Arabi was Sunni, although his writings on the Twelve Imams were also popularly received among Shia. It is debated whether or not he ascribed to the Zahiri madhab which was later merged with the Hanbali school.

After his death, Ibn Arabi's teachings quickly spread throughout the Islamic world. His writings were not limited to the Muslim elites, but made their way into other ranks of society through the widespread reach of the Sufi orders. Arabi's work also popularly spread through works in Persian, Turkish, and Urdu. Many popular poets were trained in the Sufi orders and were inspired by Arabi's concepts.

Other scholars in his time like al-Munawi, Ibn 'Imad al-Hanbali and al-Fayruzabadi all praised Ibn Arabi as ''A righteous friend of Allah and faithful scholar of knowledge'', ''the absolute mujtahid without doubt'' and ''the imam of the people of shari'a both in knowledge and in legacy, the educator of the people of the way in practice and in knowledge, and the shaykh of the shaykhs of the people of truth though spiritual experience dhawq and understanding''.

Family

Ibn Arabi's paternal ancestry was from the Arabian tribe of Tayy, and his maternal ancestry was North African Berber. Al-Arabi writes of a deceased maternal uncle, Yahya ibn Yughan al-Sanhaji, a prince of Tlemcen, who abandoned wealth for an ascetic life after encountering a Sufi mystic. His father, ‘Ali ibn Muḥammad, served in the Army of Muhammad ibn Sa'id ibn Mardanish, the ruler of Murcia. When Ibn Mardanis died in 1172 AD, his father shifted allegiance to the Almohad Sultan, Abū Ya’qub Yusuf I, and returned to government service. His family then relocated from Murcia to Seville. Ibn Arabi grew up at the ruling court and received military training.

As a young man Ibn Arabi became secretary to the governor of Seville. He married Maryam from an influential family.

Education

Ibn Arabi writes that as a child he preferred playing with his friends to spending time on religious education. He had his first vision of God in his teens and later wrote of the experience as "the differentiation of the universal reality comprised by that look". Later he had several more visions of Jesus and called him his "first guide to the path of God".

His father, on noticing a change in him, had mentioned this to philosopher and judge, Ibn Rushd Averroes, who asked to meet Ibn Arabi. Ibn Arabi said that from this first meeting, he had learned to perceive a distinction between formal knowledge of rational thought and the unveiling insights into the nature of things. He then adopted Sufism and dedicated his life to the spiritual path. When he later moved to Fez, in Morocco, where Mohammed ibn Qasim al-Tamimi became his spiritual mentor. In 1200 he took final leave from his master Yūsuf al-Kūmī, then living in the town of Salé.

Pilgrimage to Mecca

Ibn Arabi left Spain for the first time at age 36 and arrived at Tunis in 1193. While there, he received a vision in the year 1200 instructing him to journey east. After a year in Tunisia, he returned to Andalusia in 1194. His father died soon after Ibn Arabi arrived at Seville. When his mother died some months later he left Spain for the second time and traveled with his two sisters to Fez, Morocco in 1195. He returned to Córdoba, Spain in 1198, and left Spain crossing from Gibraltar for the last time in 1200. After visiting some places in Maghreb, he left Tunisia in 1201 and arrived for the Hajj in 1202. He lived in Mecca for three years, and there began writing his work Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya – 'The Meccan Illuminations.

Journeys north

After spending time in Mecca, he traveled throughout Syria, Palestine, Iraq and Anatolia.

In 1204, Ibn Arabi met Shaykh Majduddīn Isḥāq ibn Yusuf, a native of Malatya and a man of great standing at the Seljuk court. This time Ibn Arabi was traveling north; first, they visited Medina and in 1205 they entered Baghdad. This visit offered him a chance to meet the direct disciples of Shaykh ‘Abd al-Qadir Jīlani. Ibn Arabi stayed there only for 12 days because he wanted to visit Mosul to see his friend ‘Ali ibn ‘Abdallah ibn Jami’, a disciple of the mystic Qaḍib al-Ban 471-573 AH/1079-1177 AD. There he spent the month of Ramadan and composed Tanazzulat al-Mawsiliyya, Kitab al-Jalal wa’l-Jamal, "The Book of Majesty and Beauty" and Kunh ma ll Budda lil-MuridMinhu.

Return south

In the year 1206 Ibn Arabi visited Jerusalem, Mecca and Egypt. It was his first time that he passed through Syria, visiting Aleppo and Damascus.

Later in 1207 he returned to Mecca where he continued to study and write, spending his time with his friend Abu Shuja bin Rustem and family, including Nizam.

The next four to five years of Ibn Arabi's life were spent in these lands and he also kept traveling and holding the reading sessions of his works in his own presence.

Death

On 22 Rabi‘ al-Thani 638 AH 8 November 1240 at the age of seventy-five, Ibn Arabi died in Damascus.

Islamic law

Although Ibn Arabi stated on more than one occasion that he did not blindly follow any one of the schools of Islamic jurisprudence, he was responsible for copying and preserving books of the Zahirite or literalist school, to which there is fierce debate whether or not Ibn Arabi followed that school. Ignaz Goldziher held that Ibn Arabi did in fact belong to the Zahirite or Hanbali school of Islamic jurisprudence. Hamza Dudgeon claims that Addas, Chodkiewizc, Gril, Winkel and Al-Gorab mistakenly attribute to Ibn ʿArabi non-madhhabism.

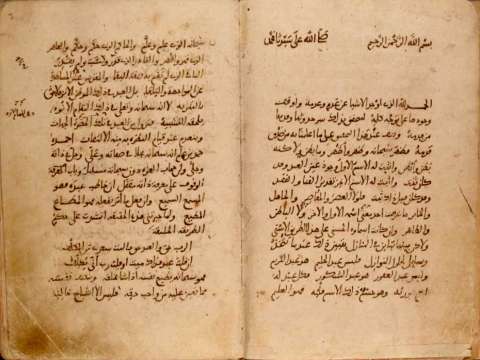

On an extant manuscript of Ibn Ḥazm, as transmitted by Ibn ʿArabī, Ibn ʿArabī gives an introduction to the work where he describes a vision he had:

I saw myself in the village of Sharaf near Siville; there I saw a plain on which rose an elevation. On this elevation the Prophet stood, and a man whom I did not know, approached him; they embraced each other so violently that they seemed to interpenetrate and become one person. Great brightness concealed them from the eyes of the people. ‘I would like to know,’ I thought, ‘who is this strange man.’ Then I heard some one say: ‘This is the traditionalist ʿAlī Ibn Ḥazm.’ I had never heard Ibn Ḥazm’s name before. One of my shaykhs, whom I questioned, informed me that this man is an authority in the field of science of Hadeeth.

Goldziher says, “The period between the sixth hijri and the seventh century seems also to have been the prime of the Ẓāhirite school in Andalusia.”

Ibn Arabi did delve into specific details at times and was known for his view that religiously binding consensus could only serve as a source of sacred law if it was the consensus of the first generation of Muslims who had witnessed revelation directly.

Ibn Arabi also expounded on Sufi Allegories of the Sharia building upon previous work by Al-Ghazali and al-Hakim al-Tirmidhi.

Al-Insan al-kamil

The doctrine of perfect man Al-Insān al-Kāmil is popularly considered an honorific title attributed to Muhammad having its origins in Islamic mysticism, although the concept's origin is controversial and disputed. Arabi may have first coined this term in referring to Adam as found in his work Fusus al-hikam, explained as an individual who binds himself with the Divine and creation.

Taking an idea already common within Sufi culture, Ibn Arabi applied deep analysis and reflection on the concept of a perfect human and one's pursuit in fulfilling this goal. In developing his explanation of the perfect being, Ibn Arabi first discusses the issue of oneness through the metaphor of the mirror.

In this philosophical metaphor, Ibn Arabi compares an object being reflected in countless mirrors to the relationship between God and his creatures. God's essence is seen in the existent human being, as God is the object and human beings the mirrors. Meaning two things; that since humans are mere reflections of God there can be no distinction or separation between the two and, without God the creatures would be non-existent. When an individual understands that there is no separation between humans and God they begin on the path of ultimate oneness. The one who decides to walk in this oneness pursues the true reality and responds to God's longing to be known. The search within for this reality of oneness causes one to be reunited with God, as well as, improve self-consciousness.

The perfect human, through this developed self-consciousness and self-realization, prompts divine self-manifestation. This causes the perfect human to be of both divine and earthly origin. Ibn Arabi metaphorically calls him an Isthmus. Being an Isthmus between heaven and Earth, the perfect human fulfills God's desire to be known. God's presence can be realized through him by others. Ibn Arabi expressed that through self-manifestation one acquires divine knowledge, which he called the primordial spirit of Muhammad and all its perfection. Ibn Arabi details that the perfect human is of the cosmos to the divine and conveys the divine spirit to the cosmos.

Ibn Arabi further explained the perfect man concept using at least twenty-two different descriptions and various aspects when considering the Logos. He contemplated the Logos, or "Universal Man", as a mediation between the individual human and the divine essence.

Ibn Arabi believed Muhammad to be the primary perfect man who exemplifies the morality of God. Ibn Arabi regarded the first entity brought into existence was the reality or essence of Muhammad al-ḥaqīqa al-Muhammadiyya, master of all creatures, and a primary role-model for human beings to emulate. Ibn Arabi believed that God's attributes and names are manifested in this world, with the most complete and perfect display of these divine attributes and names seen in Muhammad. Ibn Arabi believed that one may see God in the mirror of Muhammad. He maintained that Muhammad was the best proof of God and, by knowing Muhammad, one knows God.

Ibn Arabi also described Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and all other prophets and various Awliya Allah Muslim saints as perfect men, but never tires of attributing lordship, inspirational source, and highest rank to Muhammad. Ibn Arabi compares his own status as a perfect man as being but a single dimension to the comprehensive nature of Muhammad. Ibn 'Arabi makes extraordinary assertions regarding his own spiritual rank, but qualifying this rather audacious correlation by asserting his "inherited" perfection is only a single dimension of the comprehensive perfection of Muhammad.

Reaction

The reaction of Ibn 'Abd as-Salam, a Muslim scholar respected by both Ibn Arabi's supporters and detractors, has been of note due to disputes over whether he himself was a supporter or detractor. All parties have claimed to have transmitted Ibn 'Abd as-Salam's comments from his student Ibn Sayyid al-Nas, yet the two sides have transmitted very different accounts. Ibn Taymiyyah, Al-Dhahabi and Ibn Kathir all transmitted Ibn 'Abd as-Salam's comments as a criticism, while Fairuzabadi, Al-Suyuti, Ahmed Mohammed al-Maqqari and Yusuf an-Nabhani have all transmitted the comments as praise.

Works

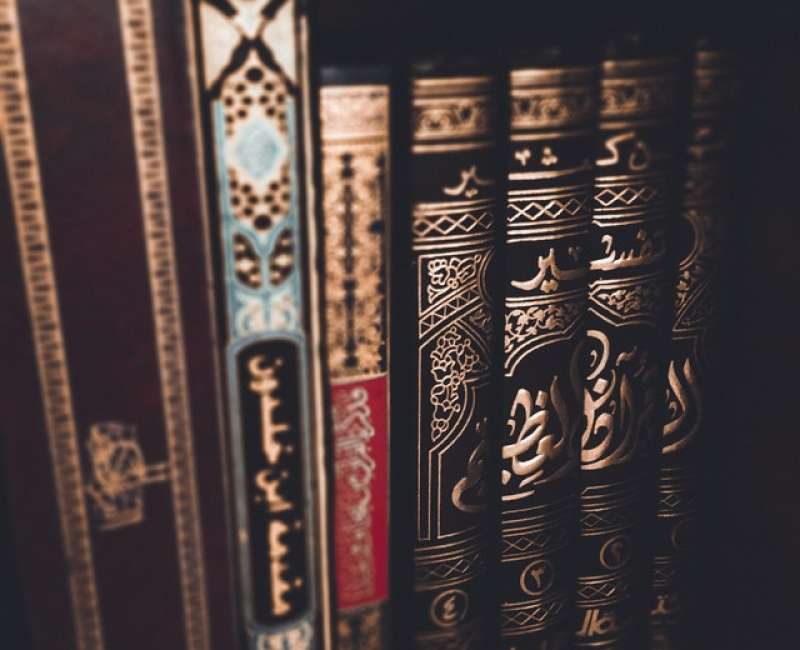

Some 800 works are attributed to Ibn Arabi, although only some have been authenticated. Recent research suggests that over 100 of his works have survived in manuscript form, although most printed versions have not yet been critically edited and include many errors. A specialist of Ibn 'Arabi, William Chittick, referring to Osman Yahya's definitive bibliography of the Andalusian's works, says that, out of the 850 works attributed to him, some 700 are authentic while over 400 are still extant.

- The Meccan Illuminations Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya, his largest work in 37 volumes originally and published in 4 or 8 volumes in modern times, discussing a wide range of topics from mystical philosophy to Sufi practices and records of his dreams/visions. It totals 560 chapters. In modern editions it amounts to some 15 000 pages.

- The Ringstones of Wisdom also translated as The Bezels of Wisdom, or Fusus al-Hikam. Composed during the later period of Ibn 'Arabi's life, the work is sometimes considered his most important and can be characterized as a summary of his teachings and mystical beliefs. It deals with the role played by various prophets in divine revelation. The attribution of this work Fusus al-Hikam to Ibn Arabi is debated and in at least one source is described as a forgery and false attribution to him reasoning that there are 74 books in total attributed to Sheikh Ibn Arabi of which 56 have been mentioned in "Al Futuhat al-Makkiyya" and the rest mentioned in the other books cited therein. However many other scholars accept the work as genuine.

- The Diwan, his collection of poetry spanning five volumes, mostly unedited. The printed versions available are based on only one volume of the original work.

- The Holy Spirit in the Counselling of the Soul Ruh al-quds, a treatise on the soul which includes a summary of his experience from different spiritual masters in the Maghrib. Part of this has been translated as Sufis of Andalusia, reminiscences and spiritual anecdotes about many interesting people whom he met in al-Andalus.

- Contemplation of the Holy Mysteries Mashahid al-Asrar, probably his first major work, consisting of fourteen visions and dialogues with God.

- Divine Sayings Mishkat al-Anwar, an important collection made by Ibn 'Arabi of 101 hadīth qudsī

- The Book of Annihilation in Contemplation K. al-Fana' fi'l-Mushahada, a short treatise on the meaning of mystical annihilation fana.

- Devotional Prayers Awrād, a widely read collection of fourteen prayers for each day and night of the week.

- Journey to the Lord of Power Risalat al-Anwar, a detailed technical manual and roadmap for the "journey without distance".

- The Book of God's Days Ayyam al-Sha'n, a work on the nature of time and the different kinds of days experienced by gnostics

- The Fabulous Gryphon of the West 'Unqa' Mughrib, a book on the meaning of sainthood and its culmination in Jesus and the Mahdī

- The Universal Tree and the Four Birds al-Ittihad al-Kawni, a poetic book on the Complete Human and the four principles of existence

- Prayer for Spiritual Elevation and Protection 'al-Dawr al-A'la, a short prayer which is still widely used in the Muslim world

- The Interpreter of Desires Tarjumān al-Ashwaq, a collection of nasībs which, in response to critics, Ibn Arabi republished with a commentary explaining the meaning of the poetic symbols.

- Divine Governance of the Human Kingdom At-Tadbidrat al-ilahiyyah fi islah al-mamlakat al-insaniyyah.

- The Four Pillars of Spiritual Transformation Hilyat al-abdāl a short work on the essentials of the spiritual Path

The Meccan Illuminations Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya

According to Claude Addas, Ibn Arabi began writing Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya after he arrived in Mecca in 1202. After almost thirty years, the first draft of Futūḥāt was completed in December 1231 629 AH, and Ibn Arabi bequeathed it to his son. Two years before his death, Ibn ‘Arabī embarked on a second draft of the Futūḥāt in 1238 636 AH, of which included a number of additions and deletions as compared with the previous draft, that contains 560 chapters. The second draft, which the most widely circulated and used, was bequeathed to his disciple, Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi. There are many scholars attempt to translate this book from Arabic into other languages, but there is no complete translation of Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya to this day.

- Diagram of "Plain of Assembly"Ard al-Hashr on the Day of Judgment, from autograph manuscript of Futuhat al-Makkiyya, ca. 1238 photo: after Futuhat al-Makkiyya, Cairo edition, 1911.

- Diagram of Jannat Futuhat al-Makkiyya, c. 1238 photo: after Futuhat al-Makkiyya, Cairo edition, 1911.

- Diagram showing world, heaven, hell and barzakh Futuhat al-Makkiyya, c. 1238 photo: after Futuhat al-Makkiyya, Cairo edition, 1911.

The Bezels of Wisdom Fuṣūṣ al-Ḥikam

Ibn al-Arabi's work Fusus al-hikam interprets the teachings of twenty-eight prophets from Adam to Muhammad.

There have been many commentaries on Ibn 'Arabī's Fuṣūṣ al-Ḥikam: Osman Yahya named more than 100 while Michel Chodkiewicz precises that "this list is far from exhaustive." The first one was Kitab al-Fukūk written by Ṣadr al-Dīn al-Qunawī who had studied the book with Ibn 'Arabī; the second by Qunawī's student, Mu'ayyad al-Dīn al-Jandi, which was the first line-by-line commentary; the third by Jandī's student, Dawūd al-Qaysarī, which became very influential in the Persian-speaking world. A recent English translation of Ibn 'Arabī's own summary of the Fuṣūṣ, Naqsh al-Fuṣūṣ The Imprint or Pattern of the Fusus as well a commentary on this work by 'Abd al-Raḥmān Jāmī, Naqd al-Nuṣūṣ fī Sharḥ Naqsh al-Fuṣūṣ 1459, by William Chittick was published in Volume 1 of the Journal of the Muhyiddin Ibn 'Arabi Society 1982.

Critical editions and translations of Fusus al-Hikam

The Fuṣūṣ was first critically edited in Arabic by 'Afīfī 1946 that become the standard in scholarly works. Later in 2015, Ibn al-Arabi Foundation in Pakistan published the Urdu translation, including the new critical of Arabic edition.

The first English translation was done in partial form by Angela Culme-Seymour from the French translation of Titus Burckhardt as Wisdom of the Prophets 1975, and the first full translation was by Ralph Austin as Bezels of Wisdom 1980. There is also a complete French translation by Charles-Andre Gilis, entitled Le livre des chatons des sagesses 1997. The only major commentary to have been translated into English so far is entitled Ismail Hakki Bursevi's translation and commentary on Fusus al-hikam by Muhyiddin Ibn 'Arabi, translated from Ottoman Turkish by Bulent Rauf in 4 volumes 1985–1991.

In Urdu, the most widespread and authentic translation was made by Shams Ul Mufasireen Bahr-ul-uloom Hazrat Muhammad Abdul Qadeer Siddiqi Qadri -Hasrat, the former Dean and Professor of Theology of the Osmania University, Hyderabad. It is due to this reason that his translation is in the curriculum of Punjab University. Maulvi Abdul Qadeer Siddiqui has made an interpretive translation and explained the terms and grammar while clarifying the Shaikh's opinions. A new edition of the translation was published in 2014 with brief annotations throughout the book for the benefit of contemporary Urdu reader.

Legacy

In fiction

In the Turkish television series Dirilis: Ertugrul, Ibn Arabi was portrayed by Ozman Sirgood.

More facts

The Four Pillars of Spiritual Transformation: The Adornment of the Spiritually Transformed

The Sufi Path of Knowledge: Ibn Al-Arabi's Metaphysics of Imagination

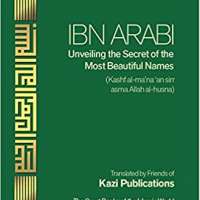

Ibn Arabi Unveiling the Secret of the Most Beautiful Names

The Tree of Being: An Ode to the Perfect Man

Dirilis: Ertugrul (2014-2019)

Looking for Muhyiddin (2014)