Diodorus Siculus (0090 B.C.-0030 B.C.)

The myths about Hades and the gods, though they are pure invention, help to make men virtuous.

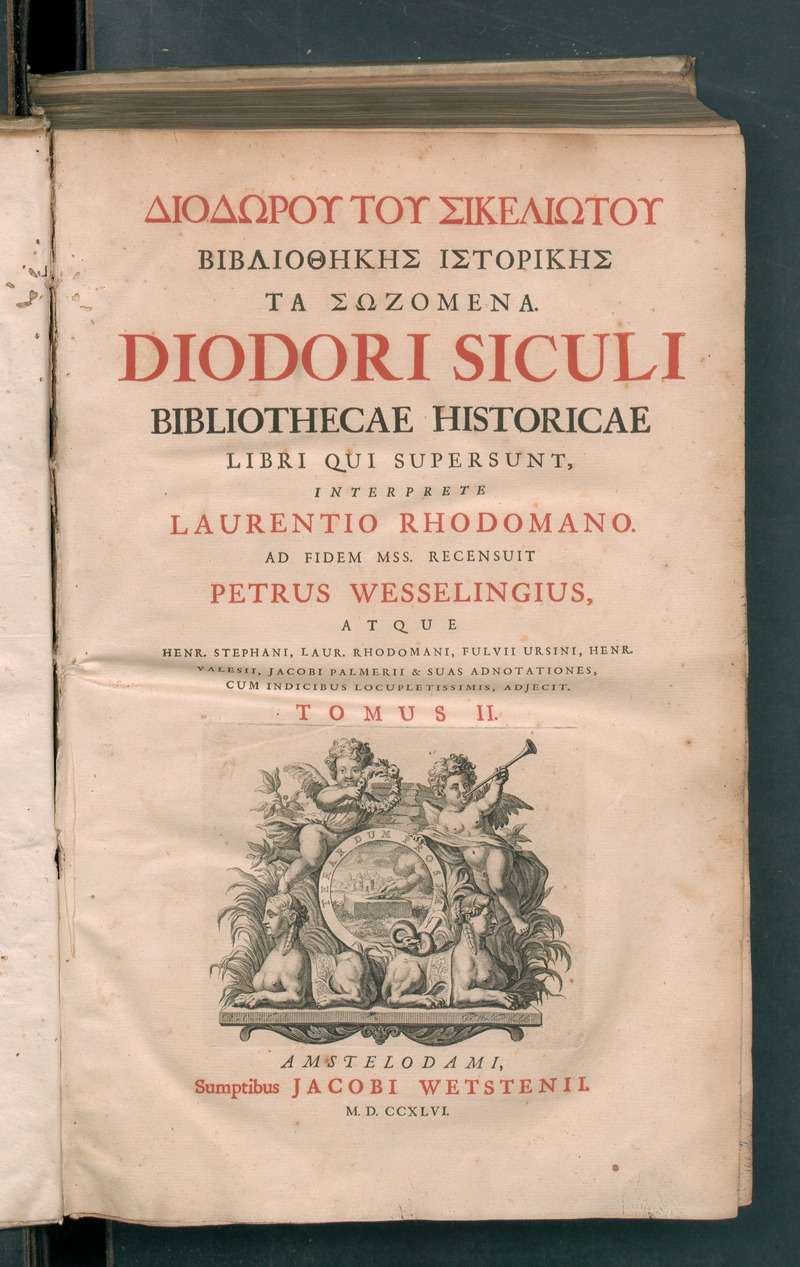

Diodorus Siculus was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history Bibliotheca historica, in forty books, fifteen of which survive intact, between 60 and 30 BC. The history broke new ground in not being Hellenocentric, partly because of Stoic influences on his belief in the brotherhood of all men.

The history is arranged in three parts. The first covers mythic history up to the destruction of Troy, arranged geographically, describing regions around the world from Egypt, India and Arabia to Europe. The second covers the time from the Trojan War to the death of Alexander the Great. The third covers the period to about 60 BC. Bibliotheca, meaning 'library', acknowledges that he was drawing on the work of many other authors.

Life

According to his own work, he was born at Agyrium in Sicily now called Agira. With one exception, antiquity affords no further information about his life and doings beyond in his work. Only Jerome, in his Chronicon under the "year of Abraham 1968" 49 BC, writes, "Diodorus of Sicily, a writer of Greek history, became illustrious". However, his English translator, Charles Henry Oldfather, remarks on the "striking coincidence" that one of only two known Greek inscriptions from Agyrium Inscriptiones Graecae XIV, 588 is the tombstone of one "Diodorus, the son of Apollonius".

Work

Diodorus' universal history, which he named Bibliotheca historica, "Historical Library", was immense and consisted of 40 books, of which 1–5 and 11–20 survive: fragments of the lost books are preserved in Photius and the excerpts of Constantine Porphyrogenitus.

It was divided into three sections. The first six books treated the mythic history of the non-Hellenic and Hellenic tribes to the destruction of Troy and are geographical in theme, and describe the history and culture of Ancient Egypt book I, of Mesopotamia, India, Scythia, and Arabia II, of North Africa III, and of Greece and Europe IV–VI.

In the next section books VII–XVII, he recounts the history of the world from the Trojan War down to the death of Alexander the Great. The last section books XVII to the end concerns the historical events from the successors of Alexander down to either 60 BC or the beginning of Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars. The end has been lost, so it is unclear whether Diodorus reached the beginning of the Gallic War as he promised at the beginning of his work or, as evidence suggests, old and tired from his labours he stopped short at 60 BC. He selected the name "Bibliotheca" in acknowledgment that he was assembling a composite work from many sources. Identified authors on whose works he drew include Hecataeus of Abdera, Ctesias of Cnidus, Ephorus, Theopompus, Hieronymus of Cardia, Duris of Samos, Diyllus, Philistus, Timaeus, Polybius, and Posidonius.

Details

- His book on Egypt, besides accounts of education, medicine, and Egyptian animal worship, included the inscription of Osymandias - “If anyone wishes to know how mighty I am and where I lie, let him surpass any of my works” - which was Shelley’s inspiration for his poem Ozymandias.

- Diodorus provides a fuller account of the half-century preceding the Peloponnesian War than Thucydides, and a more extensive, and arguably less biased, account of fourth century Greece than Xenophon.

- Diodorus also provides details of Pytheas’s voyage to Britain, including data about Cornish mining, and the judgement that “The inhabitants of Britain...are simple in their habits, and far removed from the cunning and knavishness of modern man”.

- His account of gold mining in Nubia in eastern Egypt Book III Chapters 12-14 describes in vivid detail the use of slave labour in terrible working conditions, while he provides an equally sympathetic account of the slave mines in Spain. Karl Marx in Das Kapital, for his account of the overworking of slave labour, wrote “Only read Diodorus Siculus”.

- Diodorus also gave an account of the Gauls: "The Gauls are terrifying in aspect and their voices are deep and altogether harsh; when they meet together they converse with few words and in riddles, hinting darkly at things for the most part and using one word when they mean another; and they like to talk in superlatives, to the end that they may extol themselves and depreciate all other men. They are also boasters and threateners and are fond of pompous language, and yet they have sharp wits and are not without cleverness at learning." Book 5

More facts

Damon and Pythias (1962)