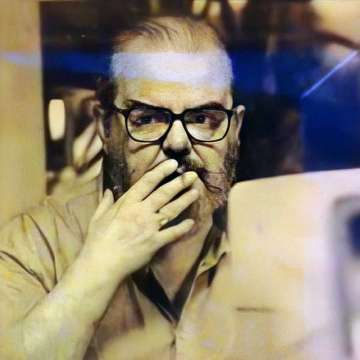

R. J. Hollingdale (1930-2001)

I admit that the generation which produced Stalin, Auschwitz and Hiroshima will take some beating, but the radical and universal consciousness of the death of God is still ahead of us. Perhaps we shall have to colonise the stars before it is finally borne in upon us that God is not out there.

Reginald John "R. J." Hollingdale was a British biographer and translator of German philosophy and literature, especially the works of Friedrich Nietzsche, Goethe, E. T. A. Hoffmann, G. C. Lichtenberg, and Schopenhauer.

Life and career

"Reg" Hollingdale dropped out of Bec Grammar School, Tooting at the age of 16 in order become a journalist, working in a junior position for a Croydon newspaper. He was called up to the Royal Air Force at a young age in the late 1940s, as part of his National Service, for two years before returning to journalism. After paying his way through private German lessons, and immersing himself in German literature and philosophy, Hollingdale earned the respect of readers and academics with his translations and studies of German cultural figures. Despite not possessing a degree, Hollingdale was elected president of a scholarly society, and was a visiting scholar at the University of Melbourne in 1991–1992. He also worked as a sub-editor at The Guardian and as a critic for The Times Literary Supplement.

Hollingdale was elected President of The Friedrich Nietzsche Society in 1989. Along with Walter Kaufmann, he was responsible for rehabilitating Nietzsche's reputation in the English-speaking world after the Second World War. Hollingdale was an atheist.

Work

Hollingdale’s best-known works focus on Nietzsche; he wrote an original biography called Nietzsche: The Man and his Philosophy (1965), a study guide to the philosopher, as well as translations of Nietzsche’s oeuvre. In addition to these achievements, he also translated works by Theodor Fontane, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Wolf Lepenies. While primarily known as a translator, Hollingdale composed scholarly essays, delivered lectures, wrote short stories, and worked for The Guardian. After his death in 2001, his family were left with a meticulously ordered collection incorporating his works in various stages of completion, alongside an equally well-organized assemblage of correspondence.

These papers found their way to Swansea University’s Richard Burton Archives in the summer of 2015, and I helped to catalogue the collection. The task gave me an opportunity to read parts of the translations, introductions, and an original short story entitled ‘Montemo in Gondola’; through this reading, an idea of Hollingdale’s personality and perspectives began to emerge – laconic, meticulous, dry humoured. For example, in his introduction to Fontane’s Before the Storm, a novel in which ‘the action contained in a six week period is divided into no fewer than 81 chapters’, he remarks that ‘until the final quarter of the book, there is hardly any action – so little, indeed, that when so trivial an incident as the nocturnal break-in at a manor house at Hohen-Vietz occurs in the 31st chapter the author entitles the chapter “something happens”’ (Hollingdale 1985). The emerging picture of the man behind the translations was confirmed by his correspondence, the extent of which demonstrates his exceptional thoroughness as he has kept nigh-on every letter he received since 1977, in addition to copies of those he sent.

For scholars whose academic interest is translation, the collection offers real insight into this highly subjective and creative process. In his library of books there are several limited editions, one of which is a book of fifteen English translations of Zarathustra’s Roundelay, which allows the reader to compare the various English adaptations of the same piece of writing. There are also numerous letters in which Hollingdale justifies his translation of a particular word, outlines his views on the art of translation, and defends his unique style. In one remarkable letter, the translator requests that his name should not appear on the publication of the Penguin centenary edition of Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams because the editor’s amendments rendered it no longer his own.

An academic working with this collection can marvel at its completeness and appreciate the potential it offers for original research, particularly in the field of translation studies.

Partial bibliography

Original works

- Nietzsche: The Man and his Philosophy 1965; 2nd rvd. edn., 2001

- Thomas Mann: A Critical Study 1973

- A Nietzsche Reader 1978

- Western Philosophy: An Introduction 1994

Translations

- Essays and Aphorisms, selections from Parerga and Paralipomena, by Arthur Schopenhauer 1973

- Elective Affinities, by Goethe 1978

- Tales of Hoffmann, by E. T. A. Hoffmann 1982

- Aphorisms, by Georg Christoph Lichtenberg 1990 ISBN 0-14-044519-6; Reprinted as The Waste Books 2000

As composed or published by Friedrich Nietzsche in chronological order:

- The Untimely Meditations 1983

- Human, All-Too-Human: A Book for Free Spirits 1986

- Daybreak 1982

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for Everyone and No One 1961.

- Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future 1973

- On the Genealogy of Morals with Walter Kaufmann 1967

- Twilight of the Idols / The Antichrist 1968

- Ecce Homo: How One Becomes What One Is 1986

- The Will to Power with Walter Kaufmann 1967

- Dithyrambs of Dionysus 2001