Leopold and Loeb (1905-1971)

To be an effective criminal defense counsel, an attorney must be prepared to be demanding, outrageous, irreverent, blasphemous, a rogue, a renegade, and a hated, isolated, and lonely person - few love a spokesman for the despised and the damned.

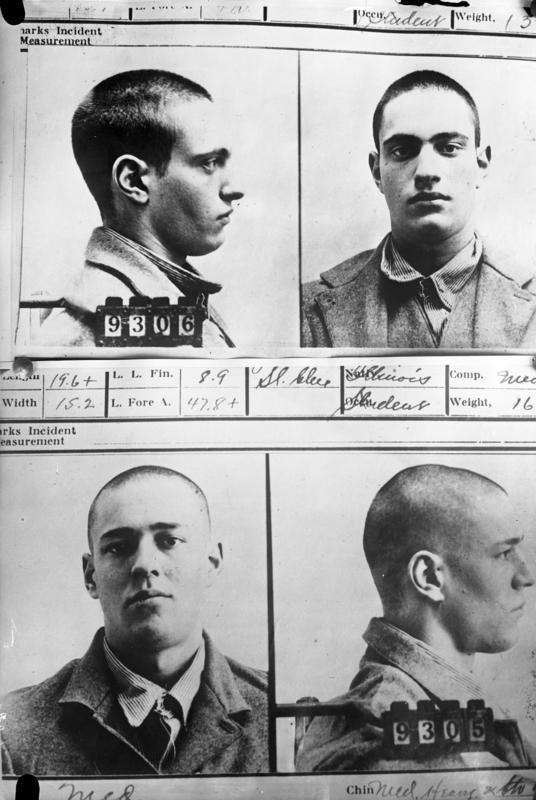

Nathan Freudenthal Leopold Jr. and Richard Albert Loeb, usually referred to collectively as Leopold and Loeb, were two wealthy students at the University of Chicago who in May 1924 kidnapped and murdered 14-year-old Bobby Franks in Chicago, Illinois, United States. They committed the murder—characterized at the time as "the crime of the century"—as a demonstration of their ostensible intellectual superiority, which, they thought, enabled them to carry out a "perfect crime" and absolve them of responsibility for their actions.

After the two men were arrested, Loeb's family retained Clarence Darrow as lead counsel for their defense. Darrow's 12-hour summation at their sentencing hearing is noted for its influential criticism of capital punishment as retributive rather than transformative justice. Both young men were sentenced to life imprisonment plus 99 years. Loeb was murdered by a fellow prisoner in 1936; Leopold was released on parole in 1958.

The Franks murder has been the inspiration for several dramatic works, including Patrick Hamilton's 1929 play Rope and Alfred Hitchcock's 1948 film of the same name. Later works, such as Compulsion 1959, adapted from Meyer Levin's 1957 novel; Swoon 1992; and Murder by Numbers 2002 were also based on the crime.

Early lives

Nathan Leopold

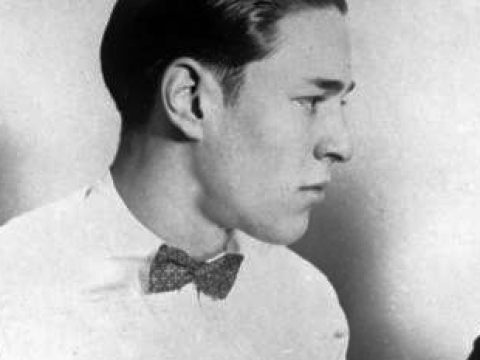

Nathan Leopold was born on November 19, 1904, in Chicago, the son of Florence Foreman and Nathan Leopold, a wealthy German Jewish immigrant family. A child prodigy, he claimed to have spoken his first words at the age of four months. At the time of the murder, Leopold had completed an undergraduate degree at the University of Chicago with Phi Beta Kappa honors and planned to begin studies at Harvard Law School after a trip to Europe. He had reportedly studied 15 languages, claimed to speak five fluently, and had achieved a measure of national recognition as an ornithologist. Leopold and several other ornithologists identified the Kirtland's warbler and made astute observations about the parasitic nesting behavior of brown-headed cowbirds, which threatened the warblers.

Richard Loeb

Richard Loeb was born on June 11, 1905, in Chicago to the family of Anna Henrietta née Bohnen and Albert Henry Loeb, a wealthy lawyer and retired vice president of Sears, Roebuck & Company. His father was Jewish and his mother was a Catholic. Like Leopold, Loeb was exceptionally intelligent. With the encouragement of his governess he skipped several grades in school and became the University of Michigan's youngest graduate at age 17. Loeb was especially fond of history and was doing graduate work in the subject at the time of his murder. Unlike Leopold, he was not overly interested in intellectual pursuits, preferring to socialize, play tennis, and read detective novels.

Adolescence, Nietzsche, and early crimes

The two young men grew up with their respective families in the affluent Kenwood neighborhood on Chicago's South Side. The Loebs owned a summer estate, now called Castle Farms, in Charlevoix, Michigan, in addition to their mansion in Kenwood, two blocks from the Leopold home.

Though Leopold and Loeb knew each other casually while growing up, they began to see more of each other in mid 1920, and their relationship flourished at the University of Chicago, particularly after they discovered a mutual interest in crime. Leopold was particularly fascinated by Friedrich Nietzsche's concept of supermen Übermenschen, interpreting them as transcendent individuals, possessing extraordinary and unusual capabilities, whose superior intellects allowed them to rise above the laws and rules that bound the unimportant, average populace. Leopold believed that he and especially Loeb were these individuals, and as such, by his interpretation of Nietzsche's doctrines, they were not bound by any of society's normal ethics or rules. In a letter to Loeb, Leopold wrote, "A superman... is, on account of certain superior qualities inherent in him, exempted from the ordinary laws which govern men. He is not liable for anything he may do."

The pair began asserting their perceived immunity from normal restrictions with acts of petty theft and vandalism. Breaking into a fraternity house at the University of Michigan, they stole penknives, a camera, and a typewriter that they later used to type their ransom note. Emboldened, they progressed to a series of more serious crimes, including arson, but no one seemed to notice. Disappointed with the absence of media coverage of their crimes, they decided to plan and execute a sensational "perfect crime" that would garner public attention and confirm their self-perceived status as "supermen."

Murder of Bobby Franks

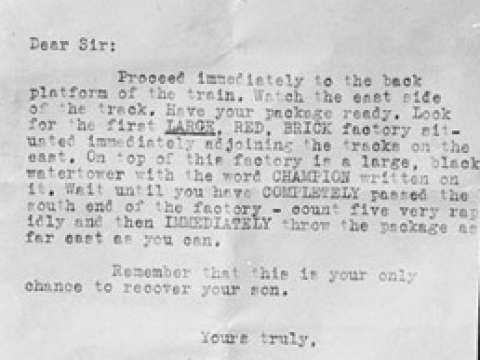

Leopold then 19 years old and Loeb 18 settled on the kidnapping and murder of an adolescent as their perfect crime. They spent seven months planning everything from the method of abduction to disposal of the body. To obfuscate the precise nature of their crime and their motive, they decided to make a ransom demand and devised an intricate plan for collecting it, involving a long series of complex delivery instructions to be communicated, one set at a time, by phone. They typed the final set of instructions involving the actual money drop in the form of a ransom note, using the typewriter stolen from the fraternity house. A chisel was selected as the murder weapon and purchased.

After a lengthy search for a suitable victim, mostly on the grounds of Harvard School for Boys in the Kenwood area, where Loeb had been educated, they decided upon Robert "Bobby" Franks, the 14-year-old son of wealthy Chicago watch manufacturer Jacob Franks. Loeb knew Bobby Franks well: Bobby was his second cousin, an across-the-street neighbor, and had played tennis at the Loeb residence several times.

The pair put their plan in motion on the afternoon of May 21, 1924. Using an automobile that Leopold had rented under the name "Morton D. Ballard", they offered Franks a ride as he walked home from school. The boy refused initially, since his destination was less than two blocks away, but Loeb persuaded him to enter the car to discuss a tennis racket that he had been using. The precise sequence of the events that followed remains in dispute, but a preponderance of opinion placed Leopold behind the wheel of the car while Loeb sat in the back seat with the chisel. Loeb struck Franks, sitting in front of him in the passenger seat, several times in the head with the chisel, then dragged him into the back seat, where he was gagged and soon died.

With the body on the floorboard out of view, Leopold and Loeb drove to their predetermined dumping spot near Wolf Lake in Hammond, Indiana, 25 miles 40 km south of Chicago. After nightfall they removed and discarded Franks' clothes, then concealed the body in a culvert along the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks north of the lake. To obscure the body's identity, they poured hydrochloric acid on his face, and also his genitals to disguise the fact that he had been circumcised.

By the time the two men returned to Chicago, word had already spread that Franks was missing. Leopold called Franks' mother, identifying himself as "George Johnson", and told her that Franks had been kidnapped; instructions for delivering the ransom would follow. After mailing the typed ransom note, burning their bloodstained clothing, and cleaning the bloodstains from the rented vehicle's upholstery the best they could, they spent the remainder of the evening playing cards.

Once the Franks family received the ransom note the following morning, Leopold called a second time and dictated the first set of ransom payment instructions. The intricate plan stalled almost immediately when a nervous family member forgot the address of the store where he was supposed to receive the next set of directions, and it was abandoned entirely when word came that Franks' body had been found. Leopold and Loeb destroyed the typewriter and burned a car robe lap blanket they had used to move the body. They then went about their lives as usual.

Chicago police launched an intensive investigation; rewards were offered for information. While Loeb went about his daily routine quietly, Leopold spoke freely to police and reporters, offering theories to any who would listen. He even told one detective, "If I were to murder anybody, it would be just such a cocky little son of a bitch as Bobby Franks."

Police found a pair of eyeglasses near the body. Though common in prescription and frame, they were fitted with an unusual hinge purchased by only three customers in Chicago, one of whom was Leopold. When questioned, Leopold offered the possibility that his glasses might have dropped out of his pocket during a bird-watching trip the previous weekend. The destroyed typewriter was recovered from Jackson Park Lagoon on June 7.

The two men were summoned for formal questioning on May 29. They asserted that on the night of the murder, they had picked up two women in Chicago using Leopold's car, then dropped them off sometime later near a golf course without learning their last names. Their alibi was exposed as a fabrication when Leopold's chauffeur told police that he was repairing Leopold's car that night while the men claimed to be using it. The chauffeur's wife later confirmed that the car was parked in the Leopold garage on the night of the murder.

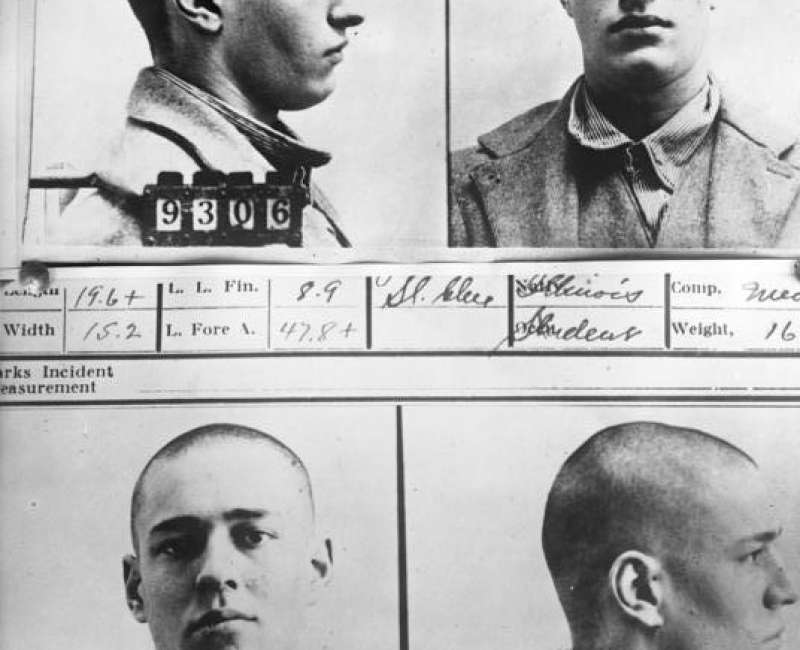

Confession

Loeb confessed first. He asserted that Leopold had planned everything and had killed Franks in the back seat of the car while Loeb drove. Leopold's confession followed swiftly thereafter, but he insisted that he was the driver and Loeb the murderer. Their confessions otherwise corroborated most of the evidence in the case. Leopold later claimed in his book long after Loeb was dead that he pleaded in vain with Loeb to admit to killing Franks. "Mompsie feels less terrible than she might, thinking you did it", he quotes Loeb as saying, "and I'm not going to take that shred of comfort away from her." While most observers believed that Loeb did indeed strike the fatal blows, some circumstantial evidence—including testimony from eyewitness Carl Ulvigh, who said he saw Loeb driving and Leopold in the back seat minutes before the kidnapping—suggested that Leopold could have been the killer.

Both Leopold and Loeb admitted that they were driven by their thrill-seeking, Übermensch delusions and their aspiration to commit a "perfect crime". Neither claimed to have looked forward to the killing itself, although Leopold admitted interest in learning what it would feel like to be a murderer. He was disappointed to note that he felt the same as ever.

Trial

The trial of Leopold and Loeb, at Chicago's Cook County Courthouse now Courthouse Place, became a media spectacle and the third—after those of Harry Thaw and Sacco and Vanzetti—to be labeled "the trial of the century." Loeb's family hired Clarence Darrow, one of the most renowned criminal defense lawyers in the country, to lead the defense team. It was rumored that Darrow was paid $1 million for his services, though he was actually paid $70,000 equivalent to $1,000,000 in 2019. Darrow took the case because he was a staunch opponent of capital punishment.

While it was generally assumed that the men's defense would be based on a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity, Darrow concluded that a jury trial would almost certainly end in conviction and the death penalty. Thus, he elected to enter a plea of guilty, hoping to convince Cook County Circuit Court Judge John R. Caverly to impose sentences of life imprisonment.

The trial technically a sentencing hearing because of the entry of guilty pleas ran for 32 days. The state's attorney, Robert E. Crowe, presented over a hundred witnesses documenting details of the crime. The defense presented extensive psychiatric testimony in an effort to establish mitigating circumstances, including childhood neglect in the form of absent parenting and, in Leopold's case, sexual abuse by a governess. Darrow called a series of expert witnesses who offered a catalogue of Leopold's and Loeb's abnormalities. One witness testified to their dysfunctional endocrine glands, another to the delusions that had led to their crime.

Darrow's speech

Darrow's impassioned twelve-hour-long "masterful plea" at the conclusion of the hearing has been called the finest speech of his career. Its principal theme was the inhumane methods and punishments of the American justice system and the youth and immaturity of the accused:

This terrible crime was inherent in his organism, and it came from some ancestor. Is any blame attached because somebody took Nietzsche's philosophy seriously and fashioned his life upon it? It is hardly fair to hang a 19-year-old boy for the philosophy that was taught him at the university.

We read of killing one hundred thousand men in a day [during World War I]. We read about it and we rejoiced in it—if it was the other fellows who were killed. We were fed on flesh and drank blood. Even down to the prattling babe. I need not tell you how many upright, honorable young boys have come into this court charged with murder, some saved and some sent to their death, boys who fought in this war and learned to place a cheap value on human life. You know it and I know it. These boys were brought up in it.

It will take fifty years to wipe it out of the human heart, if ever. I know this, that after the Civil War in 1865, crimes of this sort increased, marvelously. No one needs to tell me that crime has no cause. It has as definite a cause as any other disease, and I know that out of the hatred and bitterness of the Civil War crime increased as America had never seen before. I know that Europe is going through the same experience today; I know it has followed every war; and I know it has influenced these boys so that life was not the same to them as it would have been if the world had not made red with blood.

Your Honor knows that in this very court crimes of violence have increased growing out of the war. Not necessarily by those who fought but by those that learned that blood was cheap, and human life was cheap, and if the State could take it lightly why not the boy?

Has the court any right to consider anything but these two boys? The State says that your Honor has a right to consider the welfare of the community, as you have. If the welfare of the community would be benefited by taking these lives, well and good. I think it would work evil that no one could measure. Has your Honor a right to consider the families of these defendants? I have been sorry, and I am sorry for the bereavement of Mr. and Mrs. Franks, for those broken ties that cannot be healed. All I can hope and wish is that some good may come from it all. But as compared with the families of Leopold and Loeb, the Franks are to be envied—and everyone knows it.

Here is Leopold's father – and this boy was the pride of his life. He watched him and he cared for him, he worked for him; the boy was brilliant and accomplished. He educated him, and he thought that fame and position awaited him, as it should have awaited. It is a hard thing for a father to see his life's hopes crumble into dust.

And Loeb's the same. Here are the faithful uncle and brother, who have watched here day by day, while Dickie's father and his mother are too ill to stand this terrific strain, and shall be waiting for a message which means more to them than it can mean to you or me. Shall these be taken into account in this general bereavement?

The easy thing and the popular thing to do is to hang my clients. I know it. Men and women who do not think will applaud. The cruel and thoughtless will approve. It will be easy today; but in Chicago, and reaching out over the length and breadth of the land, more and more fathers and mothers, the humane, the kind and the hopeful, who are gaining an understanding and asking questions not only about these poor boys, but about their own – these will join in no acclaim at the death of my clients.

These would ask that the shedding of blood be stopped, and that the normal feelings of man resume their sway. Your Honor stands between the past and the future. You may hang these boys; you may hang them by the neck until they are dead. But in doing it you will turn your face toward the past. In doing it you are making it harder for every other boy who in ignorance and darkness must grope his way through the mazes which only childhood knows. In doing it you will make it harder for unborn children. You may save them and make it easier for every child that sometime may stand where these boys stand. You will make it easier for every human being with an aspiration and a vision and a hope and a fate. I am pleading for the future; I am pleading for a time when hatred and cruelty will not control the hearts of men. When we can learn by reason and judgment and understanding and faith that all life is worth saving, and that mercy is the highest attribute of man.

The judge was persuaded, though according to his ruling, his decision was based on precedent and the youth of the accused; after 12 days on September 10, 1924, he sentenced both Leopold and Loeb to life imprisonment for the murder, and an additional 99 years for the kidnapping. A little over a month later, Loeb's father died of heart failure.

Prison

Leopold and Loeb were initially held at Joliet Prison. Although they were kept apart as much as possible, the two managed to maintain a friendship behind bars. Leopold was later transferred to Stateville Penitentiary, and Loeb was eventually transferred there as well. Once reunited, the two expanded the prison school system, adding a high school and junior college curriculum.

Loeb's Death in Prison

On January 28, 1936, Loeb was attacked by fellow inmate James Day with a straight razor in a shower room and died soon after in the prison hospital. Day claimed that Loeb had assaulted him, though he was unharmed while Loeb sustained more than 50 wounds, including defensive wounds on his arms and hands; his throat had also been slashed from behind. News accounts suggested Loeb had propositioned Day; the authorities, perhaps embarrassed by publicity sensationalizing alleged decadent behavior in the prison, ruled that Day had been defending himself.

While some have claimed that newsman Ed Lahey wrote this clever lead for the Chicago Daily News – "Richard Loeb, despite his erudition, today ended his sentence with a proposition" – no evidence that this lead was ever published has been found, and actual copy from that date reads otherwise. Other newspapers at the time appeared to praise Day, who was later tried and acquitted of Loeb's murder.

A sexual motive for the killing has been suggested. There is no evidence that Loeb was a sexual predator while in prison, but Day was later caught at least once in a sexual act with a fellow inmate. In his autobiography, Life Plus 99 Years, Leopold ridiculed Day's claim that Loeb had attempted to sexually assault him. This was echoed by the prison's Catholic chaplain – a confidant of Loeb's – who said that it was more likely that Day had attacked Loeb after Loeb rebuffed his advances.

Leopold's prison life

Although Leopold continued with his work in prison after Loeb's death, he suffered from depression. He became a model prisoner and made many significant contributions to improving conditions at Stateville Penitentiary. These included reorganizing the prison library, revamping the schooling system and teaching its students, and volunteer work in the prison hospital. In 1944, Leopold volunteered for the Stateville Penitentiary Malaria Study; he was deliberately inoculated with malaria pathogens and then subjected to several experimental malaria treatments.

In the early 1950s, author Meyer Levin, a University of Chicago classmate, requested Leopold's cooperation in writing a novel based on the Franks murder. Leopold responded that he did not wish his story told in fictionalized form, but offered Levin a chance to contribute to his own memoir, which was in progress. Levin, unhappy with that suggestion, went ahead with his book alone, despite Leopold's express objections.

The novel, titled Compulsion, was published in 1956. Levin portrayed Leopold under the pseudonym Judd Steiner as a brilliant but deeply disturbed teenager, psychologically driven to kill because of his troubled childhood and an obsession with Loeb. Leopold later wrote that reading Levin's book made him "physically sick ... More than once I had to lay the book down and wait for the nausea to subside. I felt as I suppose a man would feel if he were exposed stark-naked under a strong spotlight before a large audience."

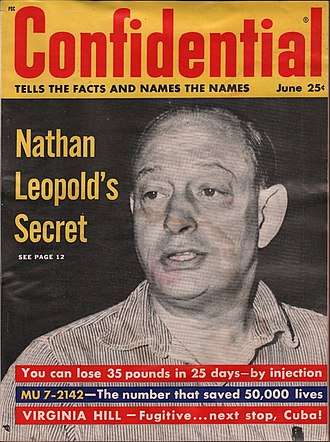

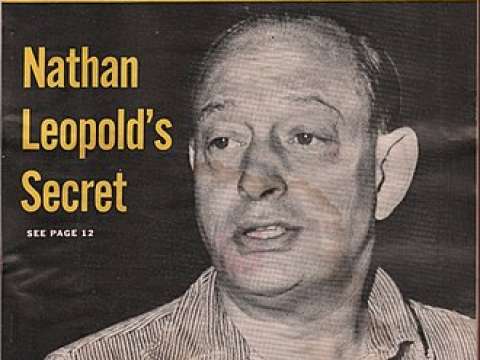

Leopold's autobiography, Life Plus 99 Years, was published in 1958, as part of his campaign to win parole. In beginning his account with the immediate aftermath of the crime, he engendered widespread criticism for his deliberate refusal expressly stated in the book to recount his childhood, or to describe any details of the murder itself. He was also accused of writing the book solely as a means of rehabilitating his public image by ignoring the dark side of his past.

In 1959, Leopold sought unsuccessfully to block production of the film version of Compulsion on the grounds that Levin's book had invaded his privacy, defamed him, profited from his life story, and "intermingled fact and fiction to such an extent that they were indistinguishable." Eventually the Illinois Supreme Court ruled against him, holding that Leopold, as the confessed perpetrator of the "crime of the century" could not reasonably demonstrate that any book had injured his reputation.

Leopold's post-prison years

After 33 years and numerous unsuccessful parole petitions, Leopold was released in March 1958. In April he attempted to set up the Leopold Foundation, to be funded by royalties from Life Plus 99 Years, "to aid emotionally disturbed, retarded, or delinquent youths." The State of Illinois voided his charter, however, on grounds that it violated the terms of his parole.

The Brethren Service Commission, a Church of the Brethren affiliated program, accepted Leopold as a medical technician at its hospital in Puerto Rico. He expressed his appreciation in an article: "To me the Brethren Service Commission offered the job, the home, and the sponsorship without which a man cannot be paroled. But it gave me so much more than that, the companionship, the acceptance, the love which would have rendered a violation of parole almost impossible." He was known as "Nate" to neighbors and co-workers at Castañer General Hospital in Adjuntas, Puerto Rico, where he worked as a laboratory and X-ray assistant.

Subsequently, Leopold moved to Santurce and married a widowed florist. He earned a master's degree at the University of Puerto Rico, then taught classes there; became a researcher in the social service program of Puerto Rico's department of health; worked for an urban renewal and housing agency; and did research on leprosy at the University of Puerto Rico's school of medicine. Leopold was also active in the Natural History Society of Puerto Rico, traveling throughout the island to observe its birdlife. In 1963, he published Checklist of Birds of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. While he spoke of his intention to write a book entitled Reach for a Halo, about his life following prison, he never did so.

Leopold died of a diabetes-related heart attack on August 29, 1971, at the age of 66. His corneas were donated.

In popular culture

The Franks murder has inspired works of film, theatre, and fiction, including the 1929 play Rope by Patrick Hamilton, performed on BBC television in 1939, and Alfred Hitchcock's film of the same name in 1948. A fictionalized version of the events formed the basis of Meyer Levin's 1956 novel Compulsion and its 1959 film adaptation. In 1957, two more fictionalized novels were released: Nothing but the Night by James Yaffe and Little Brother Fate by Mary-Carter Roberts. Never the Sinner, John Logan's 1988 play, was based on contemporary newspaper accounts of the case, and included an explicit portrayal of Leopold and Loeb's sexual relationship.

In his book Murder Most Queer 2014, theater scholar Jordan Schildcrout examines changing attitudes toward homosexuality in various theatrical and cinematic representations of the Leopold and Loeb case.

Other works influenced by the case include Richard Wright's 1940 novel Native Son, the Columbo episode "Columbo Goes To College" 1990, the CBC drama Murdoch Mysteries, Tom Kalin's 1992 film Swoon, Michael Haneke's 1997 Austrian film Funny Games and the 2008 International remake, the 2002 black comedy R.S.V.P., Barbet Schroeder's Murder by Numbers 2002, Daniel Clowes's 2005 graphic novel Ice Haven, and Stephen Dolginoff's 2005 off-Broadway musical Thrill Me: The Leopold and Loeb Story.