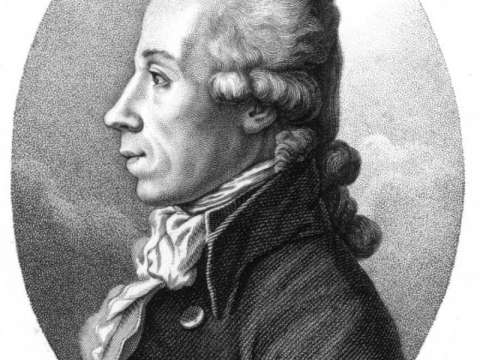

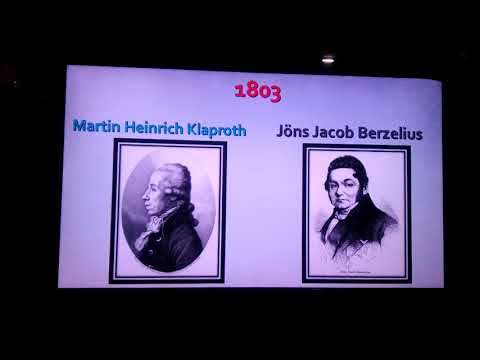

Martin Heinrich Klaproth (1743-1817)

Wherefore no name can be found for a new fossil [element] which indicates its peculiar and characteristic properties (in which position I find myself at present), I think it is best to choose such a denomination as means nothing of itself and thus can give no rise to any erroneous ideas. In consequence of this, as I did in the case of Uranium, I shall borrow the name for this metallic substance from mythology, and in particular from the Titans, the first sons of the earth. I therefore call this metallic genus TITANIUM.

Martin Heinrich Klaproth was a German chemist. He trained and worked for much of his life as an apothecary, moving in later life to the university. His shop became the second-largest apothecary in Berlin, and the most productive artisanal chemical research center in Europe.

Klaproth was a major systematizer of analytical chemistry, and an independent inventor of gravimetric analysis. His attention to detail and refusal to ignore discrepancies in results led to improvements in the use of apparatus. He was a major figure in understanding the composition of minerals and characterizing the elements. Klaproth discovered uranium 1789 and zirconium 1789. He was also involved in the discovery or co-discovery of titanium 1792, strontium 1793, cerium 1803, and chromium 1797 and confirmed the previous discoveries of tellurium 1798 and beryllium 1798.

Klaproth was a member and director of the Berlin Academy of Sciences. He was recognized internationally as a member of the Royal Society in London, the Institut de France, and the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Career

Klaproth was born in Wernigerode. He was the son of a tailor, and attended the Latin school at Wernigerode for four years.

For much of his life he followed the profession of apothecary. In 1759, when he was 16 years old, he apprenticed at Quedlinburg. In 1764, he became a journeyman. He trained in pharmacies at Quedlinburg 1759–1766; Hanover 1766–1768, with August Hermann Brande; Berlin 1768; and Danzig 1770.

In 1771, Klaproth returned to Berlin to work for Valentin Rose the Elder as manager of his business. Following Rose's death, Klaproth passed the required examinations to become senior manager. Following his marriage in 1780, he was able to buy his own establishment, the Apotheke zum Baren. Between 1782 and 1800, Klaproth published 84 papers based on researches carried out in the Apotheke's laboratory. His shop was the most productive site of artisanal chemistry investigations in Europe at that time.

Beginning in 1782, he was the assessor of pharmacy for the examining board of the Ober-Collegium Medicum. In 1787 Klaproth was appointed lecturer in chemistry to the Prussian Royal Artillery.

In 1788, Klaproth became an unsalaried member of the Berlin Academy of Sciences. In 1800, he became the salaried director of the Berlin Academy of Sciences. He sold the apothecary and moved to the academy, where he convinced the university to build a new laboratory. Upon completion in 1802, Klaproth moved the equipment from his apothecary laboratory into the new building. When the University of Berlin was founded in 1810 he was selected to be the professor of chemistry.

He died in Berlin on New Year's Day in 1817.

Contributions

An exact and conscientious worker, Klaproth did much to improve and systematise the processes of analytical chemistry and mineralogy. His appreciation of the value of quantitative methods led him to become one of the earliest adherents of the Lavoisierian doctrines outside France.

Klaproth was the first to discover uranium, identifying it first in torbernite but doing the majority of his research on it with the mineral pitchblende. On 24 September 1789 he announced his discovery to the Royal Prussian Academy of sciences in Berlin.

He also discovered zirconium in 1789, separating it in the form of its ‘earth’ zirconia, oxide ZrO2. Klaproth analyzed a brightly-colored form of the mineral called "hyacinth" from Ceylon. He gave the new element the name zirconium based on its Persian name "zargun", gold-colored.:515 Klaproth characterised uranium and zirconium as distinct elements, though he did not obtain any of them in the pure metallic state.

Klaproth independently discovered cerium 1803, a rare earth element, around the same time as Jöns Jacob Berzelius and Wilhelm Hisinger, in the winter of 1803.

William Gregor of Cornwall was the first to identify the element titanium in 1791, correctly concluding that he had found a new element in the ore ilmenite from the Menachan valley. He proposed the name "menachanite", but his discovery attracted little attention. Klaproth verified the presence of an oxide of an unknown element in the ore rutile from Hungary in 1795. Klaproth suggested the name "titanium". It was later determined that menachanite and titanium were the same element, from two different minerals, and Klaproth's name was adopted.

Klaproth clarified the composition of numerous substances until then imperfectly known, including compounds of then newly recognised elements tellurium, strontium and chromium. Chromium was discovered in 1797 by Louis Nicolas Vauquelin and independently discovered in 1798 by Klaproth and by Tobias Lowitz, in a mineral from the Ural mountains. Klaproth confirmed chromium's independent status as an element.

The existence of tellurium was first suggested in 1783 by Franz-Joseph Mueller von Reichenstein, an Austrian mining engineer who was examining Transylvanian gold samples. Tellurium was also discovered independently by Hungarian Pál Kitaibel in 1789. Mueller sent some of his mineral to Klaproth in 1796. Klaproth isolated the new substance and confirmed the identification of the new element tellurium in 1798. He credited Mueller as its discoverer, and suggested that the heavy metal be named "tellus", Latin for 'earth'.

In 1790 Adair Crawford and William Cruickshank determined that the mineral strontianite, found near Strontian in Scotland, was different from barium-based minerals. Klapworth was one of several scientists involved in the characterization of strontium compounds and minerals. Klaproth, Thomas Charles Hope, and Richard Kirwan independently studied and reported on the properties of strontianite, the preparation of compounds of strontium, and their differentiation from those of barium. In September 1793, Klaproth published on the separation of strontium from barium, and in 1794 on the preparation of strontium oxide and strontium hydroxide. In 1808, Humphry Davy became the first to successfully isolate the pure element.

Louis Nicolas Vauquelin reported the existence of a new element common to emerald and beryl in 1798, and suggested that it be named "glucine". Klaproth confirmed the presence of a new element, and became involved in a lengthy and ongoing debate over its name by suggesting "beryllia". The element was first isolated in 1828, independently by Friedrich Wöhler and Antoine Bussy. Only in 1949 did IUPAC rule exclusively in favor of the name beryllium.

Klaproth published extensively, collecting over 200 papers by himself in Beiträge zur chemischen Kenntnis der Mineralkörper 5 vols., 1795–1810 and Chemische Abhandlungen gemischten Inhalts 1815. He also published a Chemisches Wörterbuch 1807–1810, and edited a revised edition of F. A. C. Gren's Handbuch der Chemie 1806.

Klaproth became a foreign member of the Royal Society of London in 1795, and a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1804. He also belonged to the Institut de France.

The crater Klaproth on the Moon is named after him.

His son Julius was a famous orientalist.

Works

- Beiträge Zur Chemischen Kenntniss Der Mineralkörper . Vol. 1–5 . Rottmann, Berlin 1795–1810 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Chemisches Wörterbuch . Vol. 1–9 . Voss, Berlin 1807–1819 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Chemische Abhandlungen gemischten Inhalts . Nicolai, Berlin 1815 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

Bibliography

- Publication list of Klaproth

Additional Resources

- Hoppe, G; Damaschun F; Wappler G April 1987. "". Pharmazie. 42 4: 266–7. PMID 3303064.

- Sepke, H; Sepke I August 1986. "". Zeitschrift für die gesamte Hygiene und ihre Grenzgebiete. 32 8: 504–6. PMID 3535265.

- Rocchietta, S February 1967. "". Minerva Med. in Italian. 58 13: 229. PMID 5336711.

- Dann, G E July 1958. "". Svensk Farmaceutisk Tidskrift. 62 19–20: 433–7. PMID 13580811.

- Dann, G E September 1953. "". Pharmazie. 8 9: 771–9. PMID 13120350.