When the French poet André Breton penned his Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, cementing one of the most important movements of the 20th century, he claimed as his associates some of the leading avant-garde artists of the period: Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Man Ray, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso, among others. But in retrospect, one name is glaringly omitted from Breton’s selection: the Catalan painter Joan Miró.

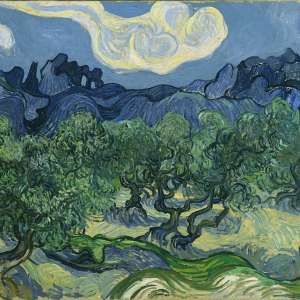

Just a year earlier, Miró, who was based between Paris and Spain, had begun work on The Tilled Field (1923) and The Hunter (Catalan Landscape) (1923–4), paintings whose fantastical, lyrical fields of uncanny references—swirling, abstract forms, floating body parts, and distorted animals—aligned closely with the concerns of the Surrealists. Indeed, the works reflected Breton’s embrace of dream imagery and “psychic automatism”: a practice that sought to give creative license to the unconscious mind through unmediated drawing or painting. Miró would incorporate this method into his work for the rest of his career.