Throughout much of the last century, a lethal and terrifying virus besieged America. Then, as now, the fear of contagion gripped ordinary Americans. And then — unlike now — a president displayed decisive leadership in fighting the virus, maintaining an unfailingly good humor and leaving the immunology to the experts.

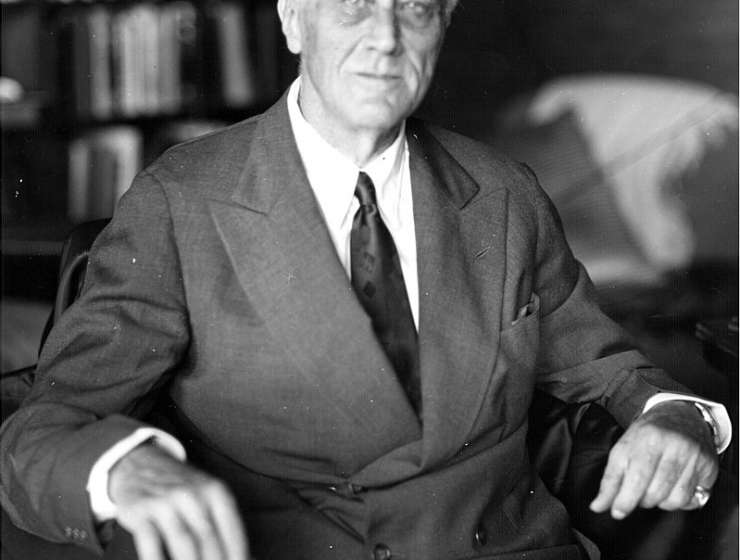

The scourge was infantile paralysis, or polio, and the president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, was its most famous victim. First clinically described in the late 19th century and persisting deep into the 20th century, the virus invaded the nervous system and destroyed the nerve cells that stimulate muscle fibers, resulting in irreversible paralysis and sometimes death.

The tally in heartbreak and death was staggering. In “Polio: An American Story,” the historian David M. Oshinsky chronicles the loss. In 1949, of the 428 cases recorded during an outbreak in San Angela, Texas, 84 victims — most of them children — were left paralyzed and 28 died.