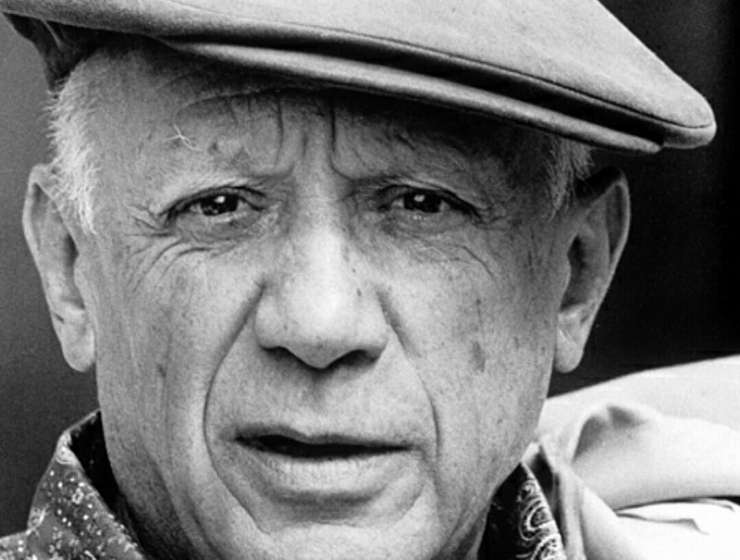

Picasso was the first rock-star artist, whose wild visions gripped the public imagination and changed 20th-century art for ever. But his flamboyant personality divided opinion. Was he a playful genius, as some suggest, or a capricious and cruel misanthrope who left battered lives in his wake? On the eve of a new show in London, we speak to his closest friends and family in a bid to unravel the enigma.

"Picasso," the surrealist poet Paul Eluard said, "paints like God or the devil." Picasso favoured the first option. "I am God," he was once heard telling himself. He muttered the mantra three times, boasting of his power to animate and enliven the visible world. Any line drawn by his hand pulsed with vitality; when he looked at it, a bicycle seat and its handlebar could suddenly turn into the horned head of a bull. But he also took a diabolical pleasure in warping appearances, deforming faces and twisting bodies, subjecting reality to a tormenting inquisition.

Picasso's behaviour was equally dualistic. In my recent conversations with people who knew him, I heard him compared to a saint, and was startled when a former model took him at his word and equated him with God. His biographer John Richardson, who lived near him in Provence during the 1950s, told me about the warmth and rollicking conviviality of the man: the genius was also genial. Others described a predator who gobbled up visual stimuli and wolfed down friends, employees and lovers.