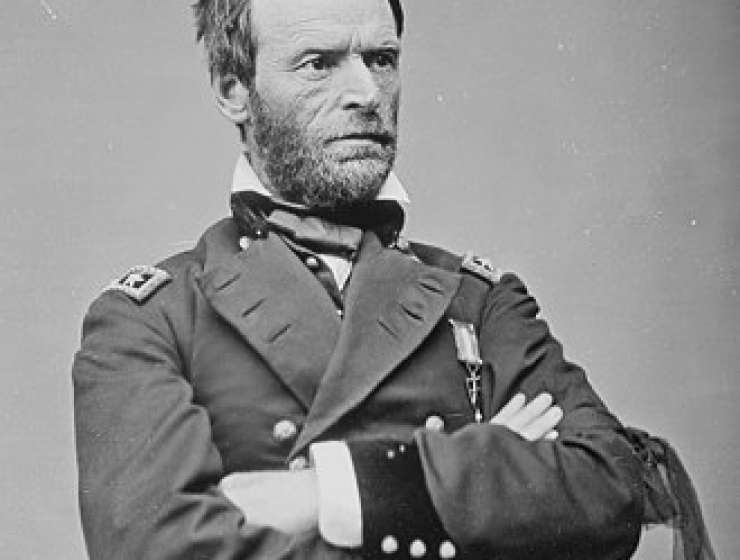

William Tecumseh Sherman’s march to the sea and burning of Atlanta are surely what distinguish him as a Civil War general, second in significance among Union officers only to Ulysses S. Grant. If Grant split the Confederacy in two during the siege and conquest of Vicksburg, Sherman (1820–91) brought the war home to thousands of Southerners. Pillaging the land and exploiting its resources, he waged what is sometimes called total war. If he did not break the South’s will to resist, he did destroy the Confederacy’s belief that it could survive as a separate entity.

As James Lee McDonough argues in “William Tecumseh Sherman: In the Service of My Country,” Sherman would have rejected the idea that he invented modern warfare. He gave orders to spare private dwellings and public structures that had no value as war-making institutions. Although, as Mr. McDonough concedes, a good deal of unsanctioned destruction occurred as more than 100,000 soldiers decimated Georgia and then the Carolinas, Sherman did punish soldiers who disobeyed his orders.

Sherman’s presumed protests notwithstanding, he was an innovator in his grasp of logistics and topography. Again and again, Southern armies took up seemingly impregnable positions, and Sherman outflanked them, drawing on his superb grasp of terrain, honed while stationed in the antebellum South. He understood Southerners very well and had even headed a military academy in Louisiana just before the fall of Fort Sumter.