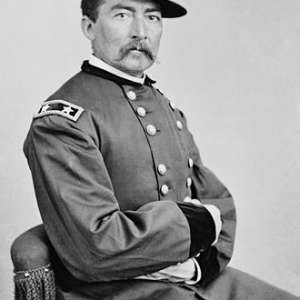

The two best-known cavalry commanders in the eastern theater of the Civil War, J. E. B. Stuart and Phil Sheridan, both seemed to enjoy considerable professional and historiographical luck, and neither appears to have entirely merited the exalted professional reputation he gained in life or death. Stuart still awaits a truly critical analysis, but Eric Wittenberg's reassessment of Sheridan pares him down to size at last, offering not only a well-deserved denunciation of his deplorable personal traits but a scathing indictment of his performance as a soldier.

The book focuses on the period between Sheridan's rise from company rank to his "finest moment" in the Appomattox campaign, with the preponderance of the text devoted to his single year with the Army of the Potomac. The first of the seven chapters encapsulates Sheridan's career in introductory fashion, but five of the other six chapters wear pejorative titles or subtitles that sound like the specifications of a court martial, and Wittenberg—an attorney, as it happens—presents the case against Sheridan precisely as though it were a legal brief. Like most such contributions to the arena of adversarial argument, Wittenberg's evidence seems one-sided and occasionally belabored, but most of it survives examination against the existing body of laudatory literature.

Wittenberg begins by complimenting Sheridan for the 1862 fight at Booneville, Mississippi, where he won his brigadier's star, and for a good defensive performance at Stone's River, but that is about all the praise he offers until the final campaign. Wittenberg faults Sheridan for repeated disobedience of orders that Sheridan (and his biographers) usually characterized as misunderstandings, and indeed those "misunderstandings" arose often enough to suggest willfulness by their very frequency. In this book Sheridan bears the blame for initiating the needless and indecisive battle of Perryville, and for abandoning the field of Chickamauga in the company of his army commander. He redeemed himself at Chattanooga, but only through insubordination: his unilateral decision to assault Missionary Ridge caught [End Page 342] his corps and army commanders unprepared, and succeeded only because of circumstances that Sheridan could probably not have predicted.