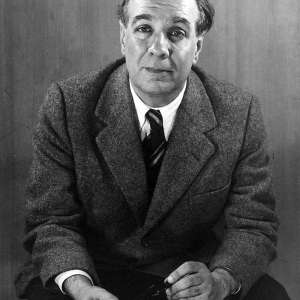

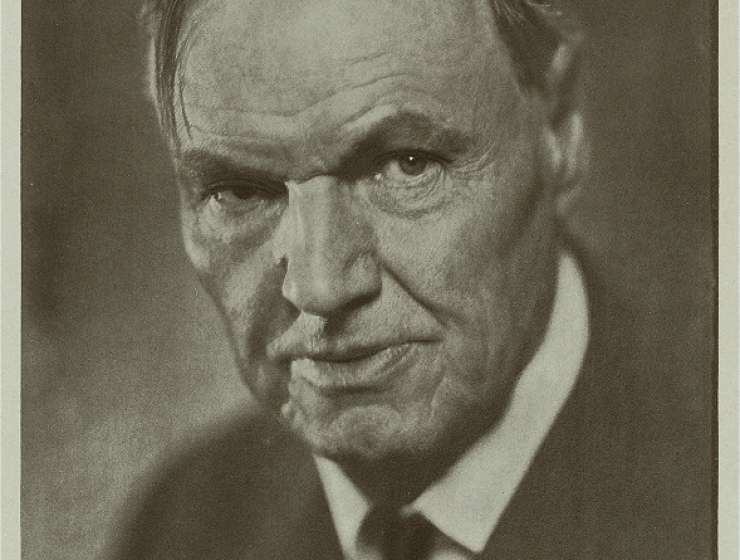

Eighty-five years ago, on 2 June 1924, during a blistering early summer in Chicago, a ravaged courtroom bruiser stepped into the future. Clarence Darrow, with his seamed face and stooped shoulders making him look every one of his 67 years, was America's greatest and most controversial defender of the lost and the damned. But, as he hunched over his desk to write to the secret love of his life, Mary Field Parton, the old lawyer felt breathless.

Earlier that day, Darrow had agreed to represent Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, two teenage lovers and the sons of Chicago millionaires, after they confessed to the world's first "thrill-killing" of a 14-year-old boy with whom Loeb had sometimes played tennis. Darrow, the Ohio-born son of an abolitionist father and suffrage-supporting mother, was himself a leading civil libertarian and vehement opponent of the death penalty. In this case, however, he confronted seemingly insurmountable odds; his disturbing and disturbed young clients faced certain execution in what newspapers would soon call the trial of the century.

In agreeing to defend Leopold and Loeb, this brilliant orator who had spent his career battling many personal demons (including a highly damaging accusation of bribing jurors) caught a glimpse of the media-driven world with which we are now so familiar. "I saw a dark vision of the future this morning," Darrow wrote to Parton, a married journalist. "This is all so shocking but, at once, I sense a strange new era. Life will become cheap and tawdry, driven by a lust for sensation and mass stupidity. Man has never been a noble beast but, now, our understanding and mercy will be tested to their limits."