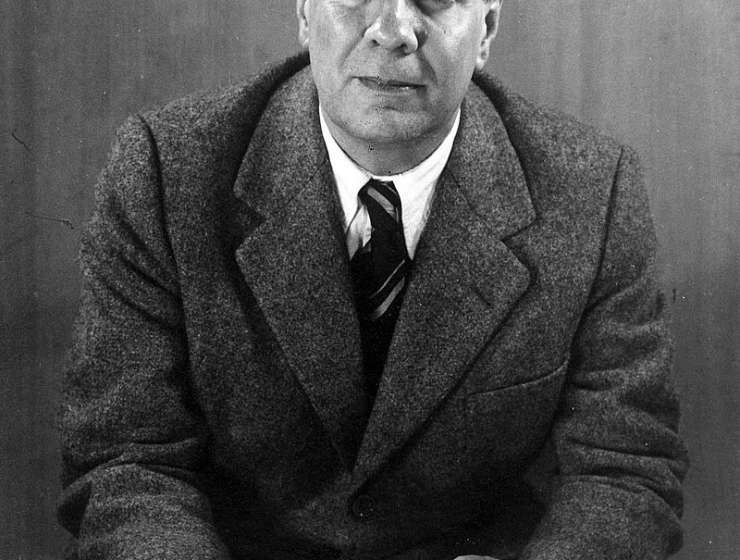

Reading the work of Jorge Luis Borges for the first time is like discovering a new letter in the alphabet, or a new note in the musical scale. His friend and sometime collaborator Adolfo Bioy Casares called his writings “halfway houses between an essay and a story”. They are fictions filled with private jokes and esoterica, historiography and sardonic footnotes. They are brief, often with abrupt beginnings. Borges’ use of labyrinths, mirrors, chess games and detective stories creates a complex intellectual landscape, yet his language is clear, with ironic undertones. He presents the most fantastic of scenes in simple terms, seducing us into the forking pathway of his seemingly infinite imagination.

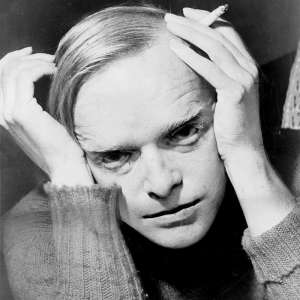

Cyber-author William Gibson describes the sensation of first reading Borges’ Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, which revolves around an encyclopedia entry on a country that appears not to exist. "Had the concept of software been available to me,” writes Gibson in his introduction to Borges’ short story collection Labyrinths, “I imagine I would have felt as though I were installing something that exponentially increased what one day would be called bandwidth.”