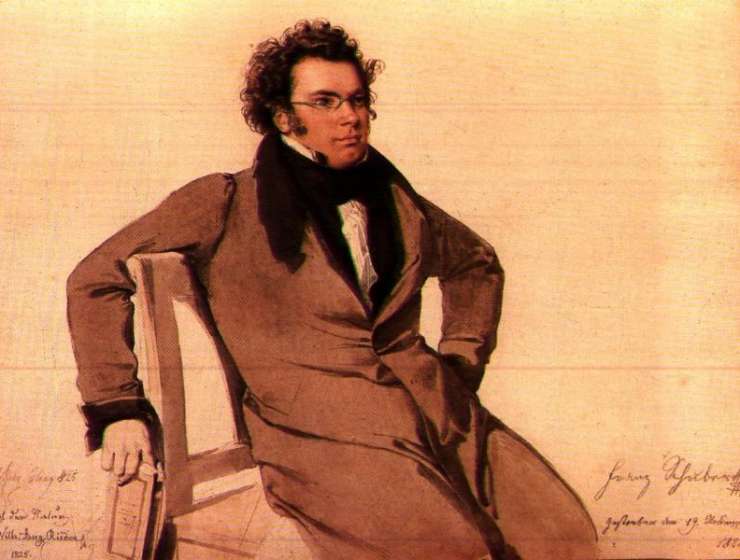

For years, CDs have arrived each week by the dozen, their styles, careers, and time periods all competing for my attention. I would get to them all eventually, I told myself — when I was idled or sick or housebound. But in these past weeks, I’ve found I have no appetite for exploration, no urge to be shaken by novel sonorities or huge orchestral dramas. Lighthearted distractions don’t distract. Instead, my musical desires have narrowed to a tiny illuminated point: a handful of Schubert’s last pieces. In the piano sonatas and chamber works he wrote a little less than 200 years ago, I hear a distillation of the world we’re all suddenly trapped in, vast and sad and radically confining.

Franz Schubert led a short but sociable life in Vienna, where he was born. He spent his 20s barhopping with friends, conducting vigorous, meandering discussions into the night. Music was the social medium of his day. Musicians and sympathetic listeners huddled around the piano, where Schubert often stationed himself for hours, unspooling that week’s output. Those who wanted to reproduce what they’d heard — or who couldn’t get entrée — could buy the sheet music, thereby supporting Vienna’s emerging gig economy of music.