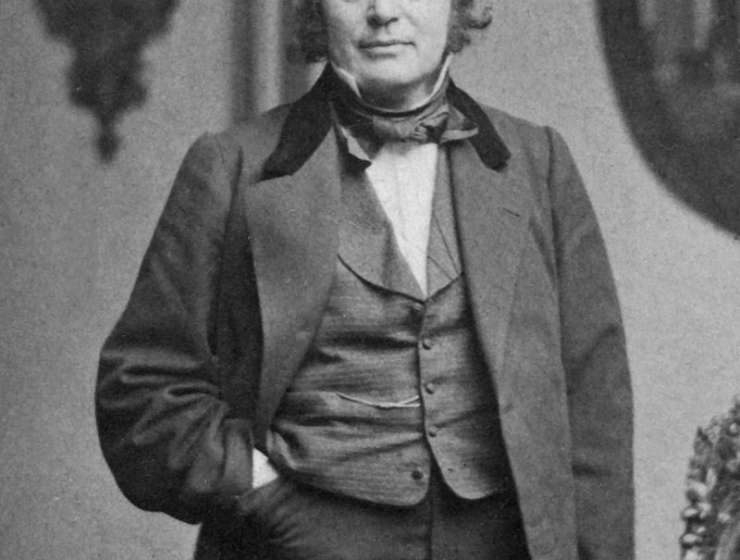

In 1847, the crowd for a lecture given by the famous Louis R. Agassiz would have been extensive — in Charleston, South Carolina, it was feverish.

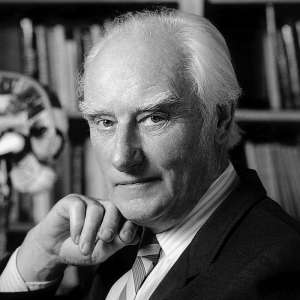

The local naturalists at The Literary Club of Charleston were preoccupied with a question they suspected only Agassiz, a newly initiated professor of zoology at Harvard, could answer: were Black and white men indeed separate species? Before he relocated to the United States, Agassiz had accepted the scientific consensus of the time, that all men belonged to the same species. But in the lectures he delivered in Cambridge, he began to hint at the more fringe theory of polygenism.

In Charleston, Agassiz took his first steps towards publicizing his theory — a decision which would forever alter his legacy as a scientist. He declared that Black people were, in profound ways, anatomically distinct from white people. He presented racist speculation after racist speculation, saying even that “the brain of the Negro is that of the imperfect brain of a seven month’s infant in the womb of a White.”