When Napoleon’s army invaded Egypt in 1798, his soldiers collected many treasures. The most famous of these was the Rosetta Stone discovered by a French soldier in 1799. This tablet comprised three versions of a decree that eventually enabled the deciphering of Egyptian hieroglyphics [1]. Ironically, the stone was captured by the British at the French surrender of Alexandria and never made it to French soil. It has been in the British Museum since 1802. Of almost equal fascination at the time was the large number of animal mummies that were brought back to France as “spoils of war.” Many species, including cats, jackals, dogs, crocodiles, snakes, ibis, and other birds, as well as human mummies, were described in exquisite detail in the Description de l’Égypte (1809–1829). Like the Rosetta Stone, many of these mummies were deposited in museums.

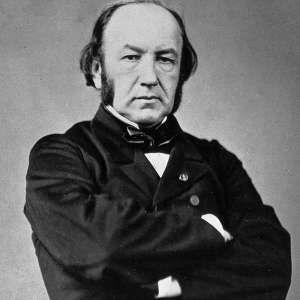

These mummies captivated the imagination of the public. Numerous “unwrappings” of human and animal mummies took place, including several ibis [2, 3]. The Egyptians mummified literally millions of these birds and stored them in vast underground catacombs [2]. In addition to the extensive military forces, the French invasion included a remarkable delegation of more than 150 civilian intellectuals, called savants, including Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, who would later become an important figure in the development of evolutionary thought. The savants established the Egyptian Institute (Institut d’Égypte) and went on to painstakingly collect and document the physical, natural, and cultural history of the region. The Sacred Ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus) mummies ignited a fierce debate about the reality of evolution between two of the giants of 19th century natural history, Georges Cuvier and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (Fig 1). This debate preceded the “Great Debate” and occurred decades before the publication of the pivotal works of Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace on natural selection and evolution.