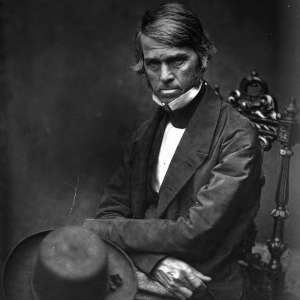

Most historians know William Henry Seward as one of the most eminent American secretaries of state. In his appraisal of the incumbents of that office, Alexander De Conde ranks Seward second in performance only to John Quincy Adams. If ever an American political leader had a record of consistently working for territorial and commercial expansion entirely by peaceful means, that man was Seward.

Yet, according to practically every historian and biographer who has written at any length about him, one striking blemish appears on his record. During an interval of several months early in 1861, a bellicose Seward invented a "foreign war panacea" for solving the problem of Southern secession and was barely thwarted by President Abraham Lincoln from bringing about such a conflict. Either Seward was possessed of an almost insane truculence or he had anticipated John Foster Dulles's brinkmanship at the worst possible time. This apparent aberration in Seward's long record of constructive statesmanship is sometimes given more emphasis in textbooks than any of his other activities in the field of diplomacy. The impression thus created is one of instability, irresponsibility, and political ambition to the point of madness.

In 1976 I wrote Desperate Diplomacy: William Henry Seward's Foreign Policy, 1861, a volume which demonstrated how absurd was the traditional portrayal of Seward as a warmonger and which showed the myth's inception in the near-paranoia of the British minister at Washington—and in machinations against Secretary Seward by Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner and other political opponents.