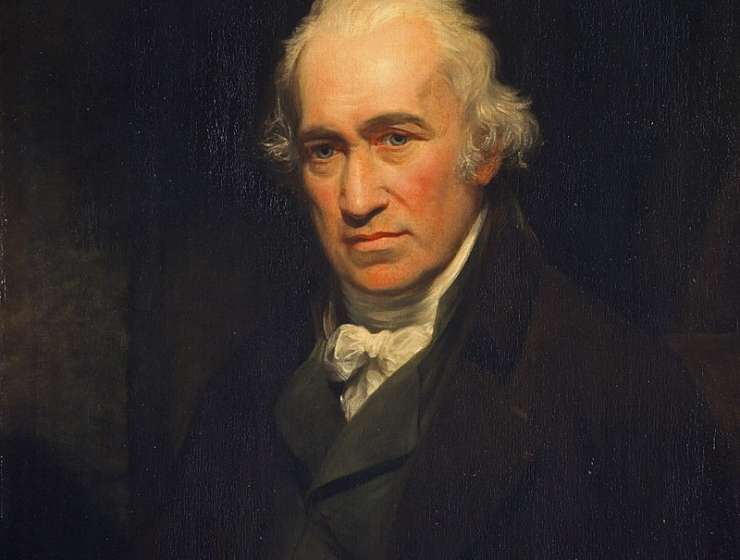

IF it be asked what James Watt did during his long, busy, and eventful life to improve ocean navigation, or to adapt the steam engine to the work of propelling ships, I am obliged to reply that I am not aware he personally did anything, or even that he concerned himself much about the matter. He took no active part that we know of in applying or adapting his steam engine to the propulsion of ships.

The reason probably was that after his attention was first directed to the subject of the steam engine, or fire engine, in 1759, his whole energy was expended, first in improving the steam engine and making its manufacture commercially successful, and afterwards in executing the orders that came for pumping and other engines that were required for mines and manufactures. In the case of most of the greatest mechanical inventions—Watt's among the number—it has not been the ideas or the inventions hy themselves that have brought success, prospeaty, or even satisfaction to their owners.

These results have had to be painfully and slowly evolved out of long and costly practical demon trations and experience of the alleged merits of the invention. James Watt toiled, suffered and endured for more than twenty years after his discovery of separate condensation in 1765, before he could see that his steam engine would ever bring him anything but disappointment, loss, and misery. It is highly characteristic, however, of Watt's fertile and original genius, and significant of what he might have done to develop the marine engine at the commencement of its history, had he taken the matter up, that upon the two principal occasions we know of when he applied his mind to the subject, he made very pregnant suggestions.