Frederick II was ill for some months before his death. Early in December 1250 a fierce attack of dysentery confined him to his hunting lodge of Castel Fiorentino in the south of Italy, which was part of his kingdom of Sicily. He made his will on December 7th, specifying that if he did not recover, he should be buried in the cathedral at Palermo, and sinking fast, died on the 13th, a few days short of his fifty-sixth birthday. He was escorted to Sicily by his Saracen bodyguard and buried in a sarcophagus of red porphyry mounted on four carved lions. The body was wrapped in cloth of red silk covered with inscrutable arabesque designs and with a crusader’s cross on the left shoulder. The tomb can still be seen in Palermo Cathedral today.

When the news reached Rome, Pope Innocent IV was delighted. ‘Let heaven exult and the earth rejoice,’ he proclaimed in a message to the Sicilian bishops and people. One of his chaplains, Nicholas of Carbio, went further. God, he wrote, seeing the desperate danger in which the storm-tossed ‘bark of Peter’ stood, snatched away ‘the tyrant and son of Satan,’ who ‘died horribly, deposed and excommunicated, suffering excruciatingly from dysentery, gnashing his teeth, frothing at the mouth and screaming…’.

However vilely expressed, the relief of the pope and his party at Frederick’s death was understandable, for the emperor had seemed to be on the verge of triumph at last in his long struggle with the papacy. Born in Italy in 1194, heir to the Hohenstaufen territories in Germany and grandson of the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, he was also the heir to the Norman kingdom of Sicily. His father died young when Frederick was two, he was crowned King of Sicily at the age of three and his mother died before he was four. At fourteen he came of age and took control of Sicily. He went on to defeat his rival for the German kingship and in 1220, aged twenty-five, he was crowned emperor in St Peter’s, Rome, by Pope Honorius III. This made him, in theory at least, the temporal head of Christ’s people on earth and the overlord of northern Italy. The fact that he was also the ruler of southern Italy and Sicily, on Rome’s doorstep, put him on collision course with the popes.

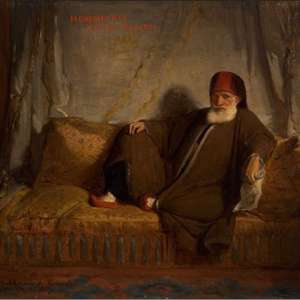

Frederick astonished his contemporaries because he was more like an oriental despot than a European king. His brilliant court at Palermo blended Norman, Arabic and Jewish elements in a culture full of the warm south. He was witty, entertaining and cruel in several different languages. He kept a harem, guarded by black eunuchs. He had dancing girls, an Arab chef and a menagerie of elephants, lions and camels. He founded towns and industries and he effficiently codified laws. A man of serious intellectual distinction, he hobnobbed amicably with Jewish and Muslim sages. He encouraged scholarship, poetry and mathematics, and original thinking in all areas. He was a fine horseman and swordsman, went coursing with leopards and panthers, and wrote the first classic medieval textbook on falconry.

Frederick’s openness to ideas made him profoundly suspect. He was supposed to have described Moses, Christ and Muhammad as a trio of deluded charlatans. His demands that the Church renounce its wealth and return to apostolic poverty and simplicity did not sit well with the papacy and its supporters, who branded him as Antichrist. Through his second wife, Yolande of Brienne, he claimed the kingdom of Jerusalem and in 1228 he led the sixth crusade to the Holy Land. Preferring diplomacy and the force of his personality to the warlike methods of earlier crusaders, he successfully negotiated with the Sultan of Egypt the hand-over of Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Nazareth. In 1229 he crowned himself King of Jerusalem in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The pope, who had excommunicated him the year before, was not pleased.

Historians used to see Frederick as a Renaissance prince born before his time, or even as the first truly modern man. Writers more recently have preferred to view him in the context of his own day. There is no doubt, however, that he astounded his contemporaries, who called him stupor mundi, ‘wonder of the world’. Such was the impact he made that many people could not believe he had really died. Stories sprang up that he had gone to the depths of Etna or a mountain in Germany where he was biding his time to return, reform the Church and re-establish the good order of the pax Romana of old. In reality his policy virtually died with him. His claim as Caesar Augustus, Imperator Romanorum, to pre-eminence over all the princes of Europe was fatally out of date.