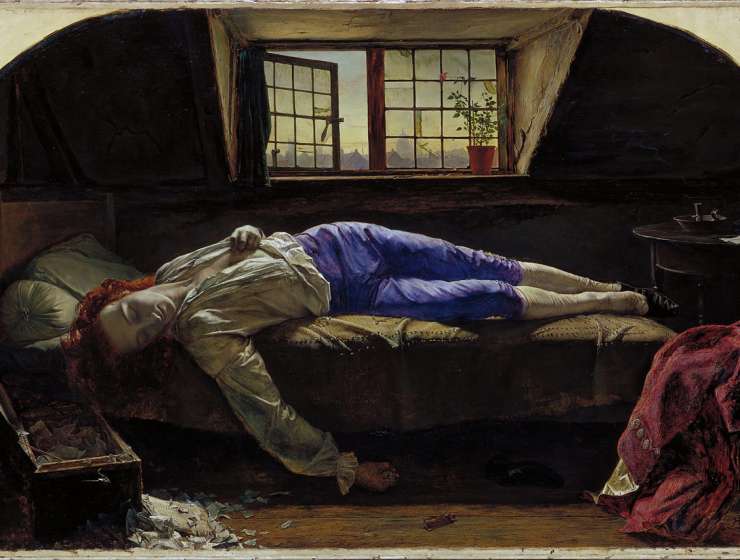

Once upon a time, Thomas Chatterton was the famous dead poet. Chatterton (1752-1770) had already been dead for decades when he was taken up like a kind of mascot by the Romantics, including William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Lord Byron.

For them, Chatterton—who famously killed himself a few months before his eighteenth birthday—was the quintessence of the tormented, misunderstood, starving poet who dies alone, young and unknown. He was the prototype of the teenage poète maudit long before Rimbaud.

Chatterton’s suicide fit with the Romantic sense of tragedy. That he might not have killed himself was beside the point. In his re-evaluation of Chatterton’s work, cultural historian Ivan Phillips notes that Chatterton may have died by accident, taking too much of what passed for medicine for his venereal disease. But Chatterton’s posthumous legend made it suicide, the epitome of the much more recent adage “live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse.” This was, after all, the era of the pan-European phenomenon of Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther. Werther’s fictional suicide had inspired a spate of actual youthful copycats.