ONE OF THE sadnesses of science education is that it is possible to take a three-year course in physics and never have to know that human beings had anything to do with it.

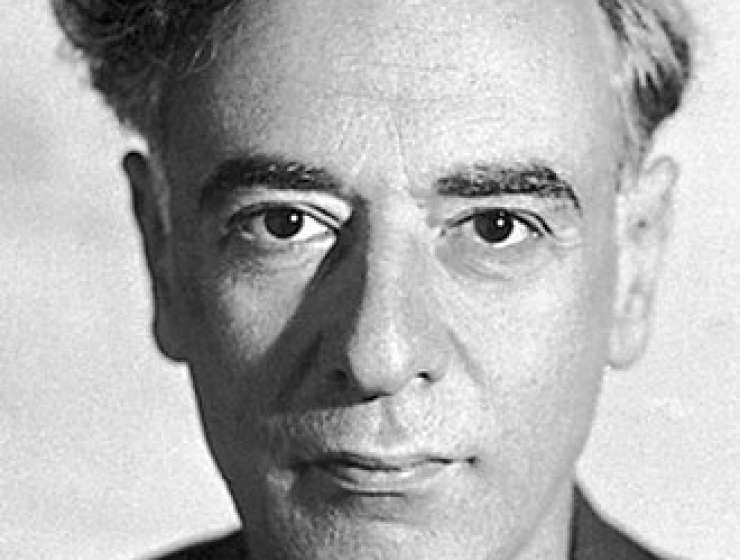

Physics hangs together so well that new insights are swiftly digested and assimilated, floating free from those who created them. The struggles of the innovators are forgotten, only their names linger as a tag for this or that effect, a label for an equation, or a symbol for an SI unit. You can study Maxwell’s equations without knowing anything about Maxwell. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle has filtered down to the cocktail party, if not the street, but how many know who Heisenberg was? Likewise Landau. As a student I briefly met a Landau theory, and there were many heavy books about Landau and Lifschitz. But no one told me who Landau was. Now I know.

Lev Davidovich Landau was one of the Soviet Union’s greatest physicists, renowned for his omniscient command of the discipline, his incisive mind and his qualities as a teacher. He appeared on the scene in the 1920s, and made important contributions to nuclear theory, solid-state physics, quantum field theory and astrophysics. He is best known for his work on the theory of superfluid helium which gained him the Nobel Prize in 1962. He died in 1968.