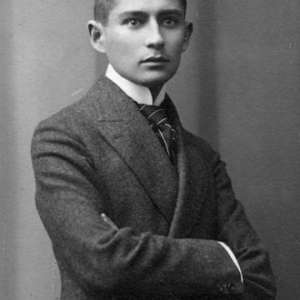

John Burroughs (b. 1837–d. 1921) was perhaps the best-known and most widely read American nature writer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but he is largely unknown and unread today. Prolific and consistent, Burroughs published scores of essays in influential large-circulation magazines between the Civil War and World War I. Such journals as Appleton’s, The Atlantic Monthly, Century, Galaxy, and Scribner’s Monthly made his reputation as important as that of Henry David Thoreau, to whom he was often compared. Unlike Thoreau, however, whose reputation grew posthumously, Burroughs earned a reputation by publishing more than thirty books during his long career. As a celebrity author of essays on natural history, especially on popular ornithology, he lived to see his essays taught widely in secondary schools in the early 20th century. Burroughs gave voice to the art of simple living and to the beauty and power of nature found near at hand.

Truly an interdisciplinary writer, Burroughs’s essays present readers with direct, concrete descriptions of nature; bluff, unsentimental evaluations of literature, especially the literature of natural history; and abstract meditations on time, the cosmos, and religion in a secular, modernizing world. Burroughs saw himself as a literary naturalist, straddling the line between nature and culture, and in his best essays he grappled successfully with the competing claims of science, religion, literature, and philosophy. Like modern writers, Burroughs faced what he called “the cosmic chill” of an indifferent universe, but he insisted that we could face the indifference and “still find life sweet under its influence” (The Light of Day). In that regard, Burroughs can be seen as an exemplary figure of the scientific imagination, in a line that would include Alexander von Humboldt and Charles Darwin.