Nicolaus Copernicus was the first to demonstrate that the earth orbited the sun, upsetting the prevailing notion that the earth was the center of the cosmos. But the Polish astronomer died in obscurity in 1543 and was buried in an unmarked grave. Five centuries later, archaeologists say they have located his long-sought resting place, under the marble floor tiles of a church.

In a sense, the search for Copernicus’ grave always led down the narrow cobblestone road into Frombork, a sleepy Polish town of about 2,500 on the Baltic coast where Copernicus lived and worked. The Frombork Cathedral, atop one of the region’s few hills, has red brick walls and a simple design. Towers built into the surrounding defensive walls, testaments to centuries of border conflicts, rise almost as high as the church, commanding a view of the town below, the Baltic Sea and sometimes a sliver of Russia ten miles to the north. A Communist-era sign with rusting planetary orbs proclaims Frombork’s former resident.

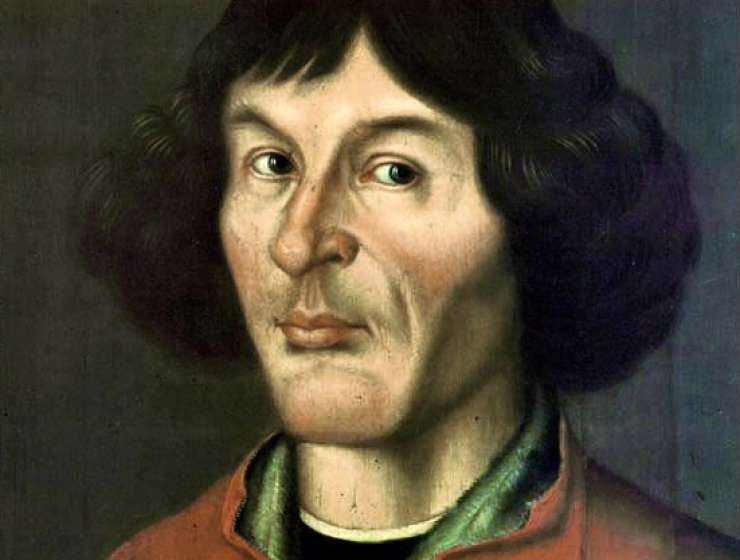

Mikolaj Kopernik (he later used the Latinized version of his name) was born in 1473 in Torun, in eastern Poland, to a comfortable merchant family. When his father died ten years later, the boy’s uncle, a bishop, oversaw his wide-ranging education, sending him to elite universities in Krakow, Bologna and Padua to prepare him for a career in the church.