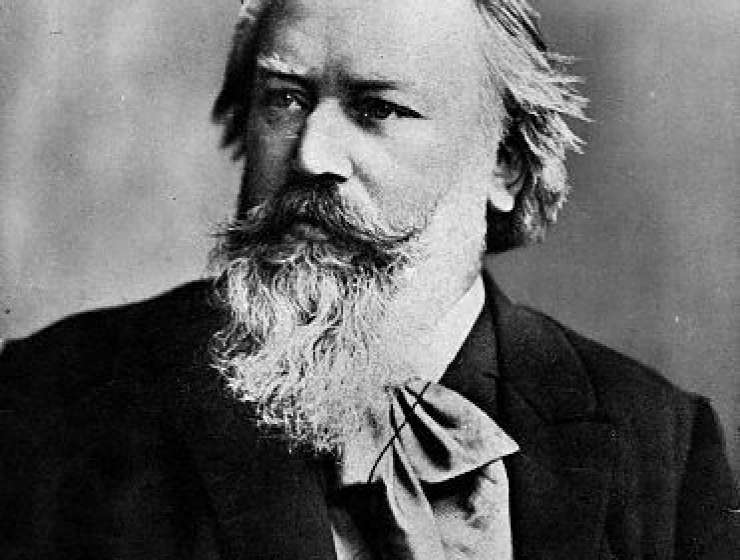

This series began last week with Beethoven. Among the composers who took up the daunting challenge of the symphonic form, none was more aware of the legacy than Johannes Brahms (1833-97). The responsibility weighed heavily upon him, and it took him many years to emerge entirely from Beethoven’s shadow.

Brahms’s works rarely feature among lists of the most well known classical tunes. But then his music never aims at instant effects; he never bothered with the distraction of opera, and he generally avoided religious music. (His German Requiem, composed following the death of his mother, uses biblical texts, but it is not a liturgical work in any real sense.) Apart from his songs – more than 200 of them – almost everything that Brahms wrote was “absolute music”, ie music that is not explicitly “about” something.