In recent years a growing number of younger social scientists, in reaction to what they conceive to be the constricting and narrow‐gauged objectivism of their elders, have engaged in a veritable orgy of subjectivism. A concern with the nuances of private experience, and with the ineffable sensibilities of peculiar selves engaged in building personal constructions of reality, has seemed at times to have almost displaced concern with the public world and the structured social order.

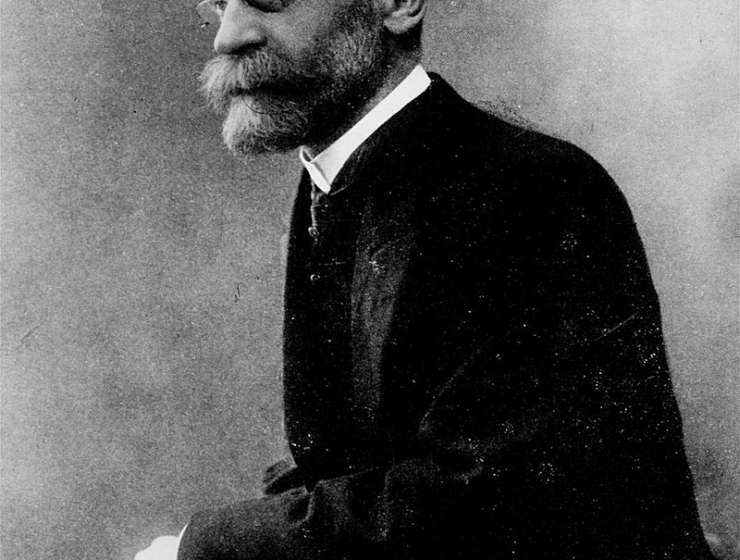

Personalistic relativism seemed to have taken command. Phenomenological sociology, ethnomethodology, reflexive sociology, cognitive anthropology and related schools of thought appeared ready to lay claim to much of the territory that earlier had been explored by students of public and objective social structures. But in the last year or two the harbingers of yet another turn in the shifts of the Zeitgeist have become discernible. The best indication of this reaction is the recent appearance of a whole series of books on the great French master of social structural sociology, Emile Durkheim.

Among these works Robert Nisbet's book shines forth as a relatively modest and yet deeply satisfying effort to highlight Durkheim's fundamental ideas. His book is not as exhaustive and far‐ranging as Steven Lukes's recent masterful intellectual biography of Durkheim, but it succeeds admirably in its stated purpose.