On the death of General Franco in 1975, Joan Miró was asked what he had done to promote opposition to the dictator, who had ruled Spain for nearly 40 years. The artist answered simply: "Free and violent things."

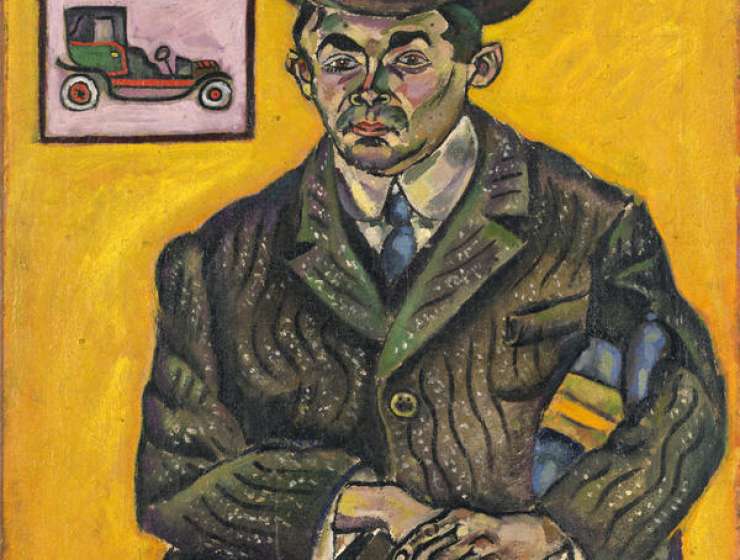

The first major Miró exhibition in this country for nearly 50 years, which opens at Tate Modern next month, will cast light on that answer. Miró is not always thought of as a political painter, in the broad or the narrow sense. He was not a creator of manifestos, or a signer of petitions; he was not given to provocative gesture like his contemporary Salvador Dali, nor did he pursue his passions at all costs, like his sometime mentor Picasso. For most of the second half of his long life (he died in 1983 at the age of 90), Miró painted in his studio in Palma, Mallorca, charting a unique course among the movements in postwar painting, and always looking very much his own man.

Politics was for Miró, however, unavoidable, an accident of birth. He was the son of a blacksmith and jeweller who lived on the harbourside in Barcelona. He came of age with the Catalan independence movement, and shared its deep-rooted sense of the possibilities of liberty. To begin with, he identified this freedom with internationalism; he longed to be in Paris. But once he had escaped, he held on to his identity as a Catalan, as a freedom fighter, all the more devoutly and from it developed an intimate visual language, which sustained him all of his working life.